“I think actors are always vastly better when they’re moving and when they realize in the course of shooting a scene that because you’ve got the Steadicam following them around they can start to forget the self-conscious side of acting. I do that with kids all the time too. Kids love to move. A Steadicam frees people up. It’s almost like it takes away the fourth wall, because people can do whatever they normally do in life, and I just chase them. I love doing that. And I find definitely the performances are much more real and organic.”

What do cannibals feasting on blood-thirsty vampires in Van Helsing and lonely singles finding love in Hallmark’s A December Bride have in common? They’re just two of the many stories film and television director David Winning has brought to the screen.

Comedy, romance, horror – David Winning does it all. In a career spanning more than 40 years David has worked on 29 different television shows including Are You Afraid of the Dark, Van Helsing, Andromeda, Stargate Atlantis, Todd and the Book of Pure Evil, Breaker High, and Earth Final Conflict. His film work has ranged from thrillers, such as Exception to the Rule starring Kim Cattrall, Sean Young and Eric McCormack, to several romantic Hallmark Channel movies such as Tulips in Spring, A December Bride, and most recently Riddle Me Dead, The 27 Hour Day, and Blake Shelton’s Time for Us to Come Home for Christmas starring Lacey Chabert.

David began his filmmaking journey shooting Super 8 movies in the backyard with his friends when he was 10 years of age. At 18, he shot his first short drama Sequence and expanded the plotline into his first feature film, STORM, produced on a shoestring budget in the summer of 1983. That film led to work on his first television series, Friday the 13th, and three Canadian Emmy Award nominations. Other awards include a national Director’s Guild award for Outstanding Drama, a 2020 Leo Award for best direction in a television movie for A Summer Romance and a 2012 Leo for best direction in a Music, Comedy or Variety Program or Series for Todd and the Book of Pure Evil.

I talked with David about his inspirations, his early days writing, producing, and directing independent features, his transition into working on movies and television shows for other producers, his approach to working with actors, and what type of work environment he creates on set for his cast and crew.

JAMES HUTCHISON

When you were 9 or 10 years old you started out doing magic shows, and then you discovered cinema, and I’m wondering if you see a connection between that initial interest in magic and your decision to start experimenting with film.

DAVID WINNING

When I was 8 we went to Disneyland, and I was begging my parents to buy me a ventriloquist dummy. We went in ’69 for the turn of the new decade – Here Come the Seventies, because I remember being there with my parents on New Year’s Eve and all the fireworks are going off and we went into the magic store – and I swear I bought a ventriloquist dummy from Steve Martin who was working there – I’ve seen pictures of him in his first job working Main Street Magic shop right off Main Street in Disneyland. It was the same guy, and I thought isn’t that weird to think that Steve Martin may have sold me my dummy.

So, I was doing ventriloquist shows and really bad comedy at school and at libraries and I was also kind of doing magic shows. And on my 10th birthday, my dad got me a little Instamatic M 22 Kodak movie camera, and all I wanted to do for the first couple of years after getting that camera was special effects. I did all these double exposure, pixilation and stop-motion films of us driving on the lawn, and animation stuff and that’s all I cared about. I didn’t think about movies as an art form or anything, I just thought about extending the world of magic into movies and photography.

And I loved going to movies, but I never really thought I’d be the kind of person to tell stories. I thought I’d be the special effects guy. You know, I’ll do all the science fiction effects and I’ll make the Starship Enterprise fly on Star Trek. So, magic and ventriloquism and puppetry and all that stuff kind of led into the narrative interest in movies. And after making films for a couple of years I thought, “Wait a minute – maybe there’s a way I can tell stories.”

JAMES

So, what do you think is the magic of movies? What do you think when you hear that term used? How would you define it?

DAVID

When you ask me that question I have to think back to what I thought was magical about movies as a kid, because it’s been so long since I remember sitting in the theatre and just forgetting time. The last time I can remember the audience just kind of fading away and getting lost in the whole experience of movies was when I was a kid and I used to go to all those crappy monster movies that used to run at the Tivoli and the Plaza theatre in Calgary in the ’70s. And then, because you’re a kid, you get so fascinated by that magic that you want to find out how it’s made and in the process of learning how to make movies and spending your life trying to transport others and give them that experience, you ruin it for yourself because you’ve seen behind the curtain.

JAMES

So, I’m wondering if you think back to that time when you were that age can you remember what it was like to sit in that dark cinema for the first time and watch 2001 A Space Odyssey.

DAVID

I must have spent a year and a half – off and on – going to the North Hill Cinerama and seeing 2001 because it was the one Cinerama screen in town. And I used to be in that giant theatre by myself just absorbed and fascinated by 2001. It’s still my favourite movie of all time, but as I’ve gotten older I’ve gotten tired of trying to explain why it’s my favourite movie because it was such a personal thing for me as a kid.

I love Kubrick. I think Kubrick’s a genius. I think that’s one of the last times I can remember feeling transported by a movie, but it’s also because 2001 is such an unusual, bizarre, visual experience that I think it’s something that transports a lot of people, just because it’s so odd and different and strangely paced, you know with beautiful imagery and stuff, but that’s kind of where it started for me – the germ of wanting to make movies and thinking of things in terms of narrative and storytelling.

JAMES

You know I think one of the strengths of 2001 and one of the reasons it still works and still fascinates is that it really tells so much of the story through visuals.

DAVID

Yup.

JAMES

There isn’t dialogue. We watch action. I suspect, because I’ve watched it recently again, that the reason it still holds your attention and still keeps you riveted and keeps you fascinated by what’s going on on-screen is because it has this sort of feeling of simplicity even though it was not necessarily simple to create.

DAVID

It’s a very simple storyline, but it’s about a huge, epic topic – the origin of mankind and the point of our existence. You know just huge, huge subject matter, but told in a very simple linear storyline.

It’s funny when you bring it up because I can remember sitting in this theatre. And it was almost like a private club because I’d go in and get a ticket and just sit there and there’d be nobody else in theatre and I’d just watch a matinee of 2001 and just be glued to it. I think I’ve seen the film sixty or seventy times, and there’s nothing like seeing it at the Cinerama. It’s a beautiful monumental epic film.

And then, strangely enough, when I was 16, I saw Star Wars for the first time in that same theatre. And I’m not the biggest Star Wars fan, but I appreciate the movie, and I remember I was a Star Wars fan from the point of view of being fascinated by George Lucas being this young wunderkind and being on the cover of Time Magazine and basically owning the summer of 1977.

I went with a bunch of my friends and we all sat in the front row and after the movie we came out of the theatre and I asked this friend of mine what did you think? And he said, “Wow, that was great.” And I said, “What other films have you liked?” And he said, “That’s the first time I’ve ever seen a movie in a theatre.”

And do you remember what an explosive kind of visceral experience it was to see Star Wars? Because the effects were so crisp and it was just so different and amazing and fantastical. Can you imagine the very first time you see a movie and it’s that movie? I can’t imagine – I just can’t imagine how much more powerful that would be than it was for the rest of us.

JAMES

We met each other at the University of Calgary on the first day of orientation. We were both in the drama department.

DAVID

This is like forty years ago.

JAMES

Yeah, this is ages ago, and one of the other filmmakers you admire is John Carpenter and I remember we’d sometimes be at the university late at night, and in the music department they had rooms where they had pianos and I remember you playing the theme to Halloween on the piano and hearing it echo down the dark corridors late at night. And that film really permeated the culture. I mean everybody knew the theme, even if they hadn’t seen the film. What do you think it was about that very small budget film that captured the attention of the movie-going public at the time?

DAVID

You see my connection to Halloween is so personal. I don’t know if it affected everybody else as much as it did me, because when Halloween came out in ’78 I was 17 and we hadn’t done Sequence yet, and I was just getting out of high school, and this guy comes along and he makes this little $300,000 movie. Up until very recently, it was the most successful independent movie of all time. It got replaced by Blair Witch Project, I think, in the ’90s and probably something else since, but when Halloween came out – I think he produced it for $320,000 and it made, like, $51 million.

JAMES

In 1978 dollars.

DAVID

Yes, and it was such an incredible inspiration for all of us because we’re thinking about doing things independently and getting things rolling and trying to get Sequence off the ground and then ultimately STORM. I just remember having this kind of brazen attitude, thinking, “If this guy can do it, then I can do it.” And I loved Carpenter, and I still love Carpenter. I think Carpenter’s a genius too.

I’ve always said, “Kubrick and Carpenter are like two ends of the spectrum. Kubrick’s a visual genius and he’s an intelligent filmmaker and Carpenter mastered putting style into bubble-gum horror movies and low budget sci-fi.” I just love his style.

He directed Starman and Escape from New York and The Thing, and I think The Thing is probably one of his greatest movies. I saw it in the theatre as a sneak preview at the Showcase Grand downtown. It was the second movie with Conan the Barbarian, which I watched, and I was really tired and then The Thing came up and just exploded. It’s one of my favourite horror, action, sci-fi movies ever. I just think it’s so well done. And one of the reasons I love it so much is because it’s not CG it’s physical effects, and I just found that so much scarier.

I think what Carpenter probably tapped into with Halloween in ’78 was that he had to hide things because he had no money. It’s like the shark in Jaws. You know there’s a monster there, but you never see it. And so, it’s a memorable scare when you do see it.

I remember you were with me when I saw Psycho for the first time at the Plaza, and I can remember sitting in a packed theatre. I’d never seen the movie before. I’d never seen it on TV. And I remember the moment where the detective is climbing the stairs – you know Martin Balsam – and it cuts to that overhead shot and mama comes rushing out from the door, and I just had this rush of adrenaline, and I was terrified, and the whole crowd’s being absolutely terrified by that movie and going, “Holy crap!”

I think John Carpenter used to do a lot of that with his early stuff. He was really good at visual suspense, and there are famous moments that I love that I’ve stolen from him millions of times. Like the shot with the babysitter in the kitchen – you know – walking from one counter to the other counter and there’s nobody in the background, and then she comes back, and he’s standing in the background, and just the static stillness of that was so scary. And I think when I was doing my first films, Sequence and STORM, I just lifted a lot of that imagery because I loved it so much.

JAMES

Do you think your own work has a certain style?

DAVID

Well, I’d probably have to only look at the films that I produced because there’s two paths to my career. There’s the independent stuff I produced that I had control over and then there’s the entire television career, where you’re making movies for somebody else. And I used to say that making movies is like trying to paint a picture and eight people are holding the paintbrush and helping you pick colours and telling you what’s wrong and what doesn’t work.

If I have a style somebody else will have to look at my work a hundred years after I’m dead and gone and say, “Oh, I see some link between all this,” because I can’t really see it anymore. I always feel like maybe this whole diversion into making other people’s movies for thirty years was supposed to bring me back to where I make my own films and actually have more control over it again.

JAMES

You’ve occasionally mentioned the desire to get back to doing those independent features, but man – that’s a long journey and a hard journey putting all the pieces together.

DAVID

In my 20s – when people are supposed to be starting families and having kids and beginning careers – I spent five years making one film, and then I spent another four years making the next film. And sometimes I think I’d love to get back to that because you have so much control over making your own projects, but at the same time, it’s really hard to raise money, and it’s hard to keep control anyway, because after I finished STORM and wanted to get it distributed I kept turning down offers for two years because people wanted to change stuff in it, and I was so idealistic in my 20s I thought, “No, you can’t change it. This is my film. I’m making this movie.”

And thank God, I held out for a decent offer from Cannon where they didn’t want to change anything but then at the end they wanted to change stuff because they said, “Here’s a quarter of a million bucks. How long is it?” “It’s 78 minutes.” “OK, deal’s off.” And there was this whole flurry of calls and I said, “Well, why don’t you advance me fifty thousand and I’ll go out and shoot more film?” And Golan-Globus and the Cannon people were like, “Yeah, whatever.” So, they advanced me the money and I ended up shooting and adding more to the film. So even with your own films before you can actually get them into the theatre you still have to make changes.

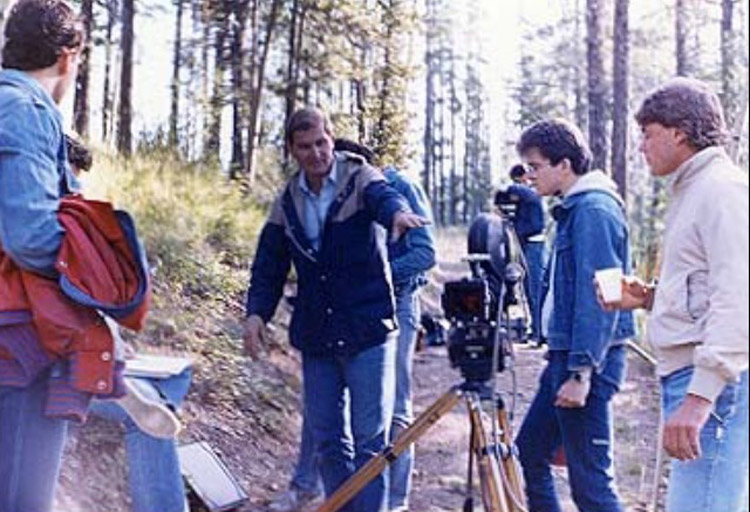

First Day – Shooting STORM

JAMES

I’m going to go back a step to when you graduated high school and you had an interest in pursuing a film career and you initially enrolled in the Drama Department at the University of Calgary – and that wasn’t right for you, and I remember you telling me you looked at the Southern Alberta Institute of Technology, but that wasn’t right for you either.

DAVID

Do you remember the joke, Jim? I did the University of Calgary for three months, I did SAIT for three weeks, and I was going to do the police academy for three days.

After I bombed out at university, I went to the film course at SAIT, and I was there for literally two days. The guy came in to speak to all the new students in the program, and I won’t mention his name because he’s probably still around, but the guy came in and I was like, “I’m going to be a film maker. I’m going to be a film director. I’m coming here to SAIT and I’m going to make movies, and I’m going to be the next Hitchcock.” And the guy came in and said, “Okay, welcome to the Cinema, Television, Stage, and Radio Arts program. If you’re here to make the next great Canadian feature film and win an Oscar you’re in the wrong place. Our goal here is to place you people in television and radio news.”

And I quit. I just said, “I quit.” And I went right to the Student Union Office and the guy came in and said, “David, this is Mr. so and so, and it’s his first day.” And he said, “Hey Dave congratulations! Welcome to SAIT. Come in and we’ll talk. It’s my first day and all I want to do is interact with the students. What can I help you with?” And I said, “I’d like to quit.” And this poor guy’s face just sunk.

JAMES

A memorable first day. Well, that led you to have a conversation with your father about your plans, right?

DAVID

Yeah, I broke his heart.

JAMES

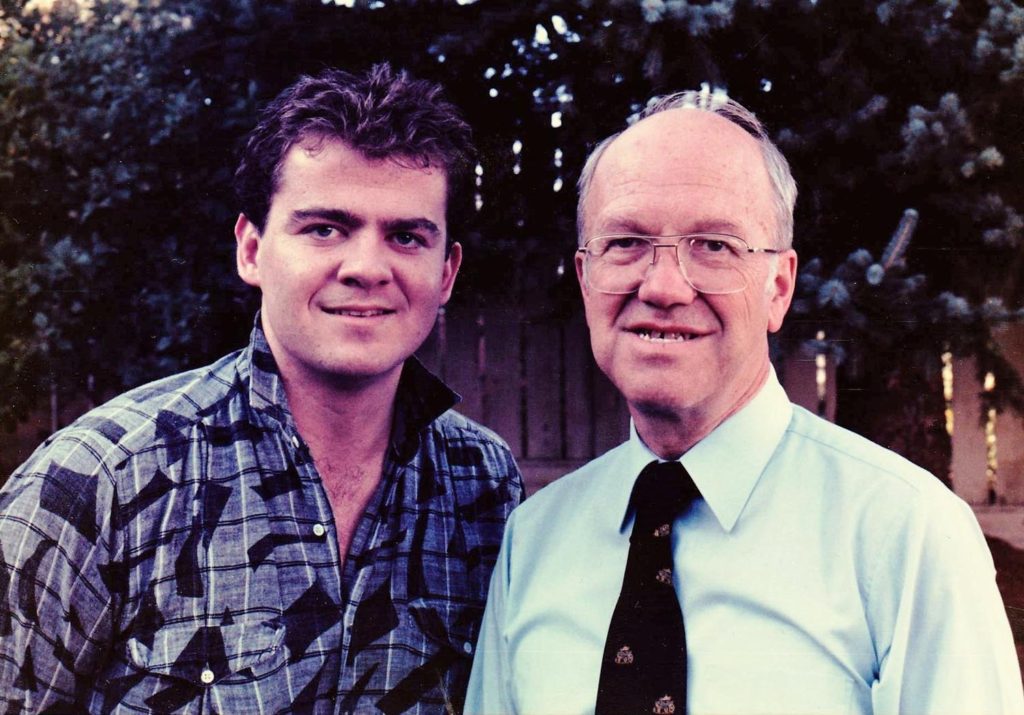

But your Dad was a pretty amazing guy. He supported your dreams, and he was willing to let you follow your path, and I just wonder if you could talk about where do you think that courage came from for you to follow your path and how did your father support that dream?

DAVID

I was 22, and I was raising money, and I was going to go to film school, and my Dad was going to help support me. I had a job as a bouncer and a ticket taker and a waiter and a bartender and all these little odds and ends jobs.

And in 1983 I had this inspiration. It was like a lightning bolt and I think I wrote a note in my diary that said, “I’m going to make my own film. I’m going to take all this money that we’ve saved for film school and buy film stock, and I’m going to go and shoot a really low ratio like three to one, and we’re going to literally force this film into existence.” Which is how I always describe STORM. Because I was so naive. I had no idea.

But I got so excited by the idea of being able to completely control a project that I remember not sleeping for weeks. “Oh my God, I can do this! I’ve had a breakthrough. I’ll write the movie, and I’ll go out and get friends and I’ll get Jim and we’ll get everybody, and we’ll hire a TV news cameraman, and we’ll go shoot the film for four weeks and we’ll shoot from dawn till the sun goes down and it’s completely mine and I make all the choices and it’s all my decisions and if it fails, I’ll just go do something else. I’ll go work in a bookstore or something.”

And that’s what led to STORM and that’s why four or five years of my 20’s was spent trying to gradually raise money to make this little epic movie. And all through that, my Dad was completely supportive, and you know he lent me money, and he charged me interest for it. And then years later when STORM sold and I paid my Dad back – every dime plus all the interest – he gave me all the interest back as a present.

And he lived long enough to see STORM, and he was proud of it. You know, I remember he came to the Uptown Theater when it ran in ’87 – when it opened in theatres, and he was with my Mom and my Mom told me years later that he sat down and he said, “Oh my God, I hope I like this.” Because he spent so much time pushing for it, and by the end he was clapping, and he loved it.

JAMES

That’s great. I know I know your Dad’s been gone a long time.

DAVID

Yeah, thirty years.

JAMES

Thirty years. What would you want him to know about your film career now?

DAVID

You know when my dad was getting sick and towards the end I’d say in my 29-year-old stupid juvenile way, “Dad, you can’t die. You’ve got to stay around. I’ve got to win my Oscar. You’ve got to see that.” And he used to say, “Well, if there’s any truth to what they say, I think I’ll know about it.”

So, I guess I’ve always sort of felt like our parents look down on us and somehow they’re aware of what we’re doing because, really, you know I mean, I had this crazy drive to make movies, but if it hadn’t been for my dad that wouldn’t have happened. And it’s not like most people think that he paid for everything but it was more about him going against the grain, because he grew up in a very academic world, you know, he had a PhD in Chemical Engineering. And my brother was in social work and my mom was a home economics major and dietitian, and so here I come along as the black sheep in the family and I was going to do something different.

And I sometimes think you’d never be able to do what you did in your 20s if you didn’t have this ridiculous bravado confidence and so, getting back to why aren’t I doing independent features now – it’s really hard. And I’m not sure we have enough energy in our 50s and 60s as we had in our 20s. I suppose I could do it, but when other people are raising money and working with corporations and all the distribution is so streamlined and you’re working with great people, you don’t really want to go back to those days where you’re hiring the news crew to make a movie.

JAMES

So, one of the fun things about getting to do STORM and getting it sold is you get to go to a premiere. What was that like?

DAVID

Oh, it was a riot. It was so much fun. It was pretty cool to actually get a movie out there and be seen. And the premiere was fun just because it was lots of family and friends. And it kind of taught me a lot about how the movie business works although everything’s changed now. But back then movies would go through this incredible cycle of a lot of hype and it’s like Barnum and Bailey and they open on Friday and then they’re gone in a week because they don’t do enough business, unless they’re a blockbuster, obviously, and they go on for months and months. STORM lasted, I think, three weeks, which I thought was amazing. But I think they kind of hung onto it because it was Canadian content, so it was playing at Westbrook and at the Showcase downtown and I took a lot of pictures of the marquees.

JAMES

And then twenty years later you did a retrospective and had a celebration and a screening and you brought the cast and crew together and did a Q&A with the audience. What was that like?

DAVID

It was great. One of the reasons I did it was because the older actors in STORM Stan Kane and Harry Freedman and Lawrence Elion were getting on and I thought it was a good reason to get everybody together and have a party, right? So why not? It was like going down memory lane but it’s not a very Canadian thing to do. Part of the reason Canadians have struggles with the film business is that they don’t promote themselves.

I think that if I’d grown up in the States I would have gone a lot further in my career a lot earlier, because it’s kind of an American sensibility to promote yourself and be big and bold, and to get your stuff out there and to ask for more, and to come back and get noticed and to get doors slammed in your face and to keep going back and keep knocking. That doesn’t happen in Canada. And I think when I was growing up I was a little more American in terms of just pushing and not taking no for an answer. And you need that in the beginning when you’re firing up your career. You need that adrenaline when you’re starting out just to get you up the mountain and get these things made.

JAMES

So, STORM led to you doing some television work. You got hired to direct a Friday the 13th episode. So, you’ve made your independent film and now you’re going to be in charge of a much larger crew. And you’re walking onto a show where people know each other. They’re working on the series, and I’m sort of wondering, what were you feeling and doing the night before you walked onto the set? And then what was the reality of actually going to work that day and calling action for the first time on a network television show?

DAVID

Scary. What was I doing the night before? Throwing up. Yeah, STORM got me into the Directors Guild and the Directors Guild had a little booklet and they put like a page for each director and stuff. And in the late ’80s, they were doing Friday the 13th and they were in their first season and one of the directors fell out and J. Miles Dale who’s gone on to produce Shape of Water and stuff, years later was one of the producers and he’s flipping through the book and he sees ‘Winning’ and he goes, “Sounds positive. Let’s hire this guy.”

So, I literally got flown to Toronto, and I was 26. And I got off the plane, got in the studio, and they’re like, “How old are you?” And I think I said, “34.” And they’re like, “Okay. You’ve done this before, right?” No. But you never tell anybody you haven’t done stuff because otherwise why would they hire you?

And I remember walking onto this amazing old house set that, I think, was built by David Cronenberg’s designer Carol Spier for one of his movies, and they had made it into the old Curious Goods store. And I was terrified, and I remember asking the first AD will you walk me around and show me stuff. And it’s a scary experience going from a crew of 20 to a crew of 180 people. And I remember asking the first AD, David McLeod, who I flew out from Toronto to work with me on the second feature Killer Image – and I asked him, “Where have you never put the camera?”

Even then I was thinking, I have to make this different – I have to make whatever I do different. I was so ballsy even then, I was like, “What have you never done here?” He told me where they usually put all the cameras and I made sure I didn’t do anything like that because you have to try to find a way to stand out.

You know, the weird kind of schizophrenic existence of directing television is that you have to stand out, but you also have to fit in. It’s not like you can come in and change the whole storyline of a series. There’s a Bible and a certain way they do things. And they don’t really want you to rock the boat, but at the same time, if you don’t stand out, how are you going to look any different than the other guys?

So that was my big thing. And so, long story short, I did three episodes of Friday the 13th, desperately trying to make them different. And I ended up getting Canadian Emmy nominations for all three episodes so somehow I was able to make those shows stand out. And I remember walking in and they said, “Here’s the script.” And it was about killer bees and the director who left actually quit because he didn’t want to do the script. And the cool thing about when you’re a young guy is you get this stuff and you’re like, “I don’t care what it is I’m going to make an amazing show out of this.”

So, I was really proud of the Friday the 13th episode I did with Art Hindle and Tim Webber. I was thrilled and terrified all at the same time. It was really scary, but one of the coolest moments is when they pay you, because it’s very lucrative and you realize, “Oh, my God I’m 26 years old, and I’m making this much money.”

And I thought, “I’m off to the races. I’m a TV director now.” And then, you know, years go by, and eventually you get to a slump, where it’s like, “Oh, you mean, I’m not just going to be handed money to do these shows?” Because it’s tricky. Every year in my career has been a tricky thing to negotiate. Every year has had its own challenge.

JAMES

So, you’ve directed all types of genres. You’ve done horror, romance, suspense, and comedy. When you look at all those different stories that you’ve brought to the screen are there any particular story elements that you feel every story shares?

DAVID

Well, you know, in one year, I’ll be doing Hallmark Christmas movies at the same time as I’m doing gruesome post-apocalyptic vampires for Netflix. And I always think everything’s the same. Kid shows are the same. Erotic thrillers are the same. The Hallmark Christmas movies, the vampire series, the westerns – they’re all the same and you’re just trying to pull people into a story, so they care about it.

So, the most important part of anything you do is the first ten minutes, because you need to pull people into the stories and make it somehow personal for them, even if it’s science fiction, or running from vampires, something that would never happen to them, you have to make the stories personal to people or else they don’t care.

I’ve spent 30 years leaning really heavily on Steadicams and the roaming process and so if a hundred years from now someone’s looking at my movies, they may notice that the camera never stops moving. So the Steadicam actually becomes like a third actor in a love story. So, for example, you have the characters actually dancing with the camera, and it’s so cool to me how it’s shorthand for me to pull people into a story.

And jumping back to the Psycho reference I was talking about earlier – remember how Hitchcock tried to give everybody this really disturbing point of view of Norman Bates – so that the audience actually felt like the murderer. The audience is spying on Marian in the shower. The audience is seeing Martin Balsam falling backwards with the knife. And that was disturbing in the ’60s, because it’s like, “Oh, my God, I’m seeing this from the perspective of a maniac.” But that’s one of the tricks I’ve always tried to do, is to make the camera kind of a character in the shows.

JAMES

In terms of directing actors does giving them movement help their performance?

DAVID

Totally, I think actors are always vastly better when they’re moving and when they realize in the course of shooting a scene that because you’ve got the Steadicam following them around they can start to forget the self-conscious side of acting. I do that with kids all the time too. Kids love to move. A Steadicam frees people up. It’s almost like it takes away the fourth wall, because people can do whatever they normally do in life, and I just chase them. I love doing that. And I find definitely the performances are much more real and organic.

JAMES

So, I was wondering about the importance of promises and payoffs in terms of putting together a film or a television show? Do you think in terms of promises and payoffs? And if you do, how does that influence things in terms of telling the story and shooting it?

DAVID

I’m not really a writer, right? I’m a director, so I’m basically always interpreting someone else’s writing. But when I read movie of the week scripts, I have to kind of draw on the writer side of me to improve them. One of the revelations I made early in my career was when I realized the bottom line with almost any production company I’ve worked for is, that as long as it doesn’t cost them more money, nobody really cares if you rewrite the scripts. So, then you think, I’ve been given this gift, I can change this. So, I guess I do have to rely on a lot of writing skills.

And in terms of payoffs, what comes to mind when you ask me the question is the structure of the script I’m working on, and if the structure isn’t exciting enough I end up trying to inject elements to make things better in terms of cliff-hangers or story suspense, and just basically trying to find any way to improve and elevate the material, which is always what you try to do.

I’m definitely trying to create builds and payoffs for characters and constantly trying to make the characters less shallow. You try to flesh out the characters and make the characters more interesting so that everybody has some kind of an arc. And the most interesting characters to me are always the villains and you try to give the villain some humanity and some backstory because I think one note villains are pretty boring. Not that there’s a lot of villains in Hallmark movies.

JAMES

There are obstacles.

DAVID

There are obstacles. It’s usually saving the farm or falling in love. That’s always an obstacle.

JAMES

Who’s a favourite villain, then?

DAVID

You know my favourite villain of all time is Laurence Olivier as Szell in Marathon Man. And I like Javier Bardem as the creepy face-shifting Bond villain in Skyfall, and that movie has probably become one of my favourite movies of all time in terms of the action genre. When I saw Skyfall, I thought, that’s it. That’s the perfect three-act structure for a modern epic action film. I just loved it. I thought the whole thing was amazing.

You know, we were talking about my favourite directors, Kubrick and Carpenter, earlier but my other two favorites that we didn’t mention, and I think they’re the best screenwriters in the world – if I may go out on a limb – are the Coen Brothers. I love the Coen Brothers’ movies. Always have loved them. I think they write poetry. And I think they’re screenwriters that actually have so much more respect for the English language and words and I just love their movies.

So, you have opposite ends of the spectrum with Kubrick and Carpenter and now I’ve got the Coen brothers on one end and on the other end of the spectrum, the low end is Tarantino. Who I also think is brilliant, but I also think his style can come off as low class, and incredibly foul-mouthed. But the movies are so visceral. I love his movies. I think his movies are just brilliantly done. And they seem so heartless, but they’re just so energetic that I just get pulled into them.

JAMES

Don’t you think he embraces that B-Movie genre?

DAVID

Well, he’s doing what I thought I was doing. He’s imitating things that he loved. Everything he does is an imitation of something that moved him a lot. So, I can remember in ’92, when I had just finished Killer Image and I thought, “Okay I made this great action film.” And I’ve got it coming out, and I was all geared up and excited, and then out came Reservoir Dogs, and I swear, I almost retired at 29. I almost quit the business when Reservoir Dogs came out because I thought that’s exactly what I’ve been trying to make for 10 years – a really visceral, violent, action-packed, nonstop, funny film. I just love Reservoir Dogs. What an explosive debut.

And the other incredible breakthrough premiere movie from my other guys was Blood Simple. You know, the Coen Brothers first movie, and in the script for Killer Image the senator was described as an Emmet Walsh type. And Emmet Walsh had been in Blood Simple and I’m thinking, “Who can I get to play this guy?” And somebody said, “Well, why don’t you just ask Emmet Walsh?” And I was like, “I can’t go to the guy who did Blood Simple. I wouldn’t even be able to talk to him.” So, you know, we approached him and he said, “Sure I’ll do it.” We had him for four days. We had Michael Ironside for seven days. And the film was twenty days. So, a whole lot of that movie is not either of those two guys. Its body doubles and over-the-shoulder shots and, you know, people running around trying to look like Michael Ironside. That’s how you make low-budget movies.

JAMES

You sent me a note that one of your favourite films of your career is Exception to the Rule, starring Sean Young, Kim Cattrall, and William Devane, and I just want to know why is that one of your favourites? Why does that one standout?

DAVID

I did STORM and Killer Image and then I did Profile for Murder with Lance Henriksen and then Exception to the Rule. Exception to the Rule was the kind of movie that I’ve always wanted to make. I always wanted to make thrillers, you know, and we mentioned, Marathon Man. That was the kind of movie I wanted to do. Thrillers.

But it’s very seldom that you actually end up exactly on the path you want when you’re trying to pay the rent and develop a career. So, you end up doing Christmas movies and vampire shows and kid’s sitcoms and dinosaur shows.

There’s this fantasy that directors are offered things and I take a script and I review it and I go, “I don’t know if I want to direct this. Oh really. How much are they offering?” It just doesn’t happen. I mean, the agent calls and says, “David, they want you for the movie.” And I say, “When?” Boom. “What’s the money?” Boom. And I go, and I do it. I take any job that’s given to me, because otherwise I would starve to death.

So, Exception to the Rule was great, because it was a thriller and it was one of those cases where the script was kind of shallow and kind of misogynistic and I said, “Can I change this?” And again, they say, “We don’t care.” As long as it doesn’t cost money, people don’t care. “Do whatever you want to do you’re the director. Rewrite it.”

So, I was able to do a little rewriting on it and make it a bit more thriller-ish, more kind of Marathon Manish, which is what I always wanted to do. And we had a slightly bigger budget on it and I just kind of felt like I found my mojo on that movie.

And I still like it. I think it still stands up. And a lot of my friends that have seen Exception to the Rule think it’s one of my better movies from those early thrillers. You know I’ve done stuff that I’m really proud of in the last 10 years, but Exception was just a really fun memory because it was shot incredibly quickly, and I was trying so hard because you’re always trying to make small movies look like big features.

And when we finished it, I thought it turned out pretty well and we ended up taking it to the Houston Film Festival and I brought down Michael Bateman who was the film editor. And we showed it to a crowd of like 500 people in the theatre and they all jumped in the right places and they really got into it. And it’s just that kind of group feeling that doesn’t happen very often. And then we talked to the audience for like an hour and a half after the movie. And it just felt like I touched people with it. It was pretty cool. And you know, I got to work with Kim Cattrall and Sean Young in the same movie and I used to brag about getting to work with William Devane from Marathon Man.

JAMES

Did you chat to him at all about Marathon Man? Did you play the fan a little bit?

DAVID

I’m always playing fanboy with these guys. Like I got to ask Emmet Walsh about Blood Simple and I was definitely a fanboy with him and with Devane too. Exception to the Rule turned out pretty well. I thought. It’s not a bad little thriller for what it was, you know.

JAMES

You had an audience of 500 people who are totally engrossed in the film. That’s what you’re trying to do.

DAVID

That’s why you make movies, right? Nowadays it doesn’t happen because there’s no theater experience anymore, but more people watch my directing work now than have ever watched it.

When I do these Hallmark movies, if I’m lucky, I can get three to five million people watching it on the first screening. And then it goes into reruns so you multiply that and you know twenty to thirty million people end up watching your work; same work that people tease me about making, but when you’re shooting them, you feel the weight of the fact that these movies really mean something to people, you know. You have to value and respect the importance of everything you’re creating. It will mean something to someone.

And I just love pushing buttons and playing with emotions and making people cry and I just love doing that in these movies. And Hallmark gives you perfect opportunities for doing that because they’re all about family and Christmas and longing. And so many of the ones I’ve done recently are about heartbreak and dealing with grief.

Like, the Time for Me to Come Home series that I did that was based on a Blake Shelton song and he executive produced for Hallmark. They did three movies. I did the first one and then someone else came in and directed the second one, and then they brought me back for the third one. Which is the one that came out last Christmas and got the biggest ratings of all three, which is great, but they’re all heartbreaking, you know, three Kleenex kind of movies.

And I tear up worse than anybody watching these movies. When you direct something, you really get into it because you’re more invested in it than anyone. You’re the best audience because you know the people and you made the choices and you suggested things that they do. So of course, the big tear-jerky moments are going to hit me the hardest because I’ve choreographed it that way.

JAMES

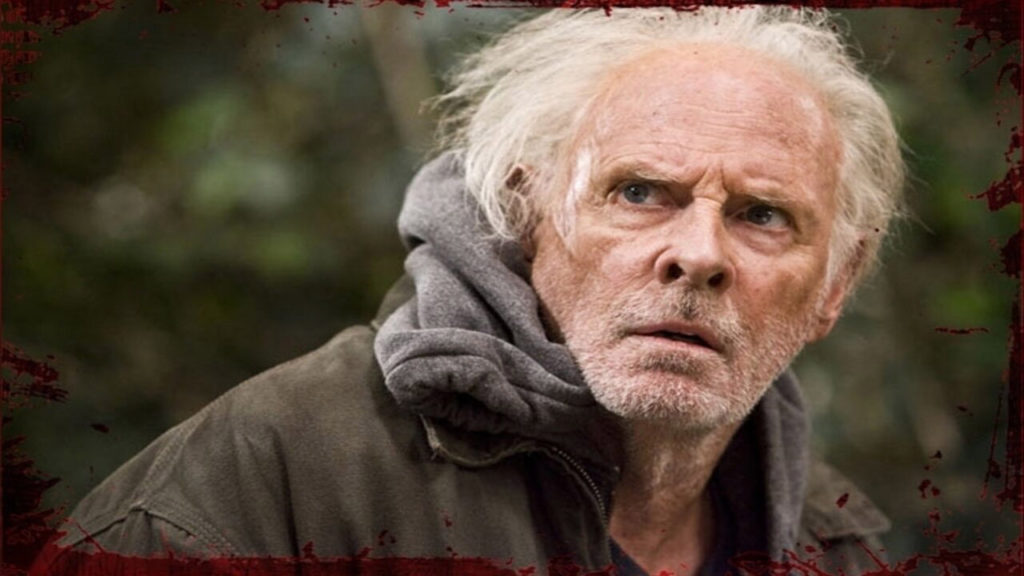

Well, I want to talk more about the Hallmark stuff but we were talking about being a fanboy and working with a few of the folks that you loved when you were growing up. So, let’s talk a little bit about Swamp Devil and good old Bruce Dern. He’s the guy from Coming Home, Black Sunday,

DAVID

…Silent Running…

JAMES

Yeah, and you know, nominated for an Oscar for Nebraska. What was it like doing Swamp Devil with Bruce Dern?

DAVID

You don’t have enough time to hear my Bruce Dern stories. When I was about 13-14-15, I wandered into Science Theater 148 at the University of Calgary where the Student’s Union used to run Friday Flicks in the ’70s. And Paul Brown, may he rest in peace, and I rode our bikes over to the university and wandered into the Science Theater, and the projectionists were doing a test screening of the movie they were running that night.

And so up comes the opening few minutes of Silent Running, which became one of my favourite movies of all time, because, you know, I was already a kid sucked into Star Trek and all the science fiction stuff and suddenly there’s this outer space movie I’d never heard of, because back in those days movies could be released and Calgary wouldn’t see them for years.

But, of course, with the internet now everything’s just instant, right? Things are released and, boom, you see it or it’s on Netflix, but back then movies would take a while to get around the world and get into people’s psyche and stuff and Silent Running was one of those movies. So, I see Bruce Dern and I’m in love with the movie and then flash forward to the early ’80s and Bruce Dern’s in Calgary shooting that movie with Gordon Lightfoot.

JAMES

The Western, right?

DAVID

Yeah, and it was called Harry Tracy Desperado.

JAMES

Right, and they were shooting at Heritage Park.

DAVID

And they were shooting at Heritage Park and we went a couple of times just to get in on the set – that was back when you could do this. And we just kind of watched them shoot and I ended up sitting down in this director’s chair and they called cut and Bruce Dern walked out of the set and came over and sat right beside me with this Styrofoam coffee cup.

And I looked at him and I wanted to say to him, “You know you’re the reason I got into movies, I love Silent Running.” And he turned and he started to talk to me and then he looked at me and said, “Oh God I’m talking to an extra.” And he got up and walked away. And then I looked down and I see his coffee cup, and there was this 10 second moment where I thought I’m going to take that coffee cup. I could sell it on eBay. This is Bruce Dern’s coffee cup from Harry Tracy.

So anyway, now flash forward years later and I’m shooting monster movies in Montreal. And we did Black Swarm with Robert Englund and then Swamp Devil was right after and we shot them together. It was like an eight-week period – we’d prep and shoot – prep and shoot. And so, this rumour started happening halfway through Black Swarm that they were going to get Bruce Dern to do Swamp Devil. And I just about lost my mind. And believe it or not, I actually did tell him that coffee cup story eventually.

So, they pick Bruce Dern up at the airport and he was coming in for his costume fitting on a Saturday and this cab pulls up and Bruce Dern gets out and he was 72, I think, when we did Swamp Devil, and he got out and I was kind of speechless. I mean I get to direct this movie, and I am in awe of this guy and I really don’t know what to say to him. He was incredible.

And he used to tell me stories all the time about movies that he worked on and things that he’d done and Silent Running and his best friend in the world is Jack Nicholson. And we would be shooting and his cell phone would ring and he’d go, “Can you take that?” Because we’re in the middle of shooting something – “Can you take that? Say hi to Jack.” And I’d take the phone and I’d look down and it would say, Jack Nicholson. He’d always hand me the phone when Nicholson phoned him. And I just never had the guts to say anything. Anyway, it was an incredible experience. Working with your idols. It’s kind of scary.

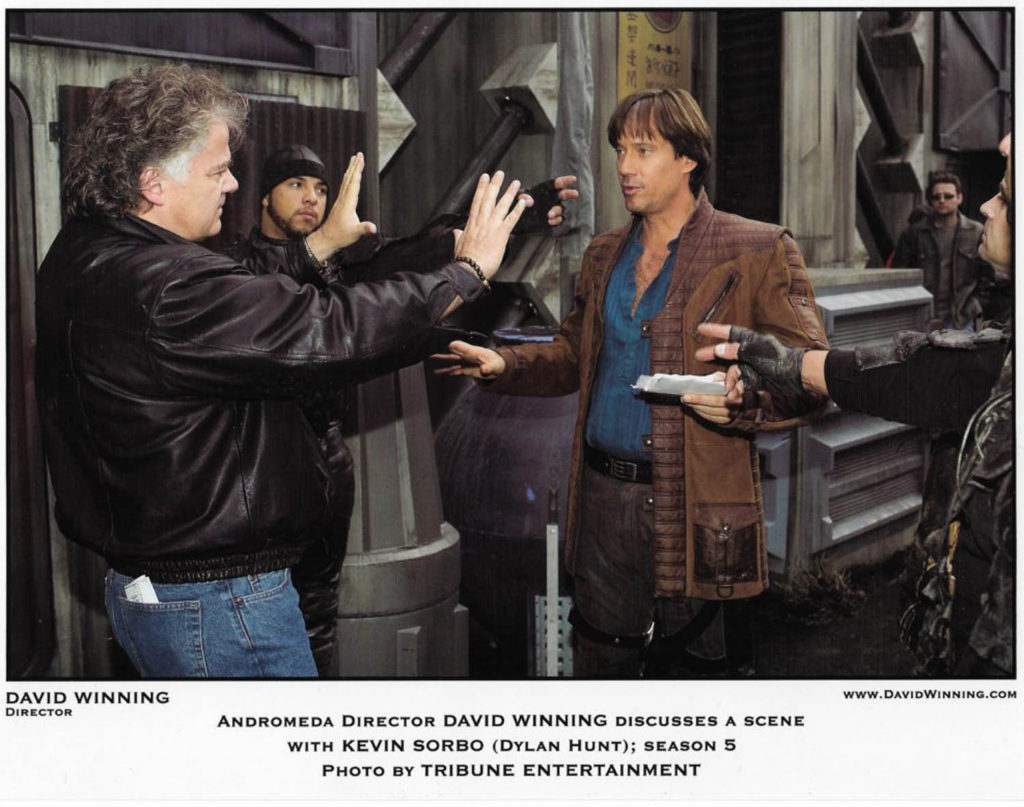

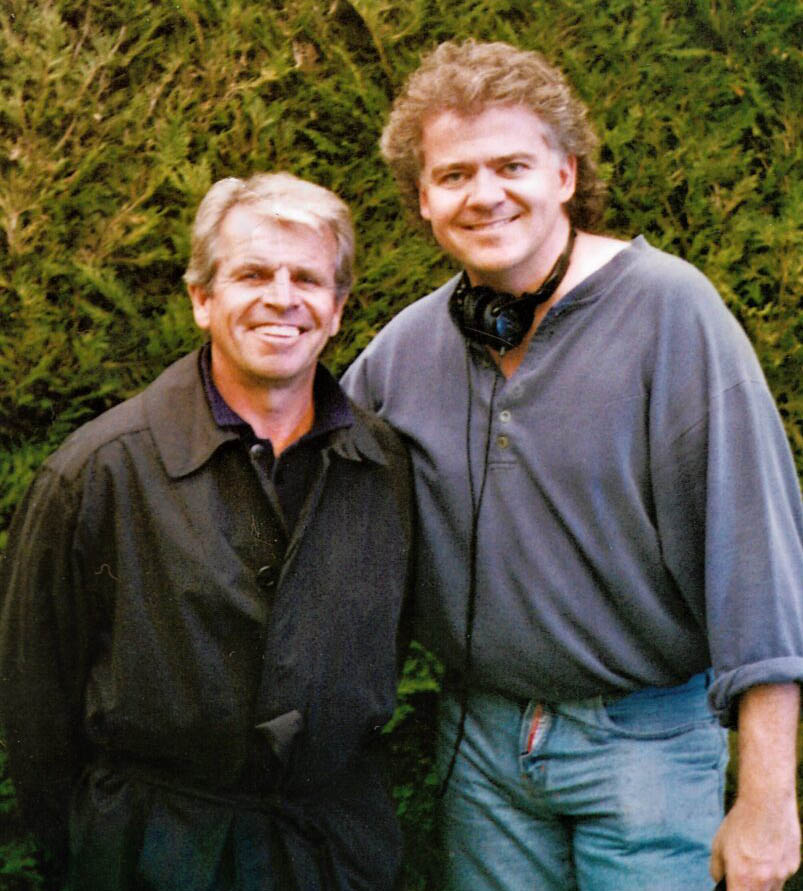

And speaking about idols in the late ’80s they called me up and said, “We’re doing this series in Toronto called Earth Final Conflict – a Gene Roddenberry series.” And I’m like, “You’re punking me, right?” Like, I’m going to work on a Gene Roddenberry series, because I grew up with Star Trek. And I’ve told millions of people that Star Trek taught me how to make movies when I was 10. And Star Trek the original series is now completely corny, and people make fun of it, but the original series is still my favourite, I remember being 10,11, and 12 and just staring at this black and white TV, trying to figure out how they put it all together and kind of reverse engineering it in terms of drama and structure and choreography and I still do stuff to this day that’s right out of Star Trek. It’s just the way my brain works when I’m trying to block scenes. And then I went out and did Andromeda for four seasons, which was another Roddenberry series.

JAMES

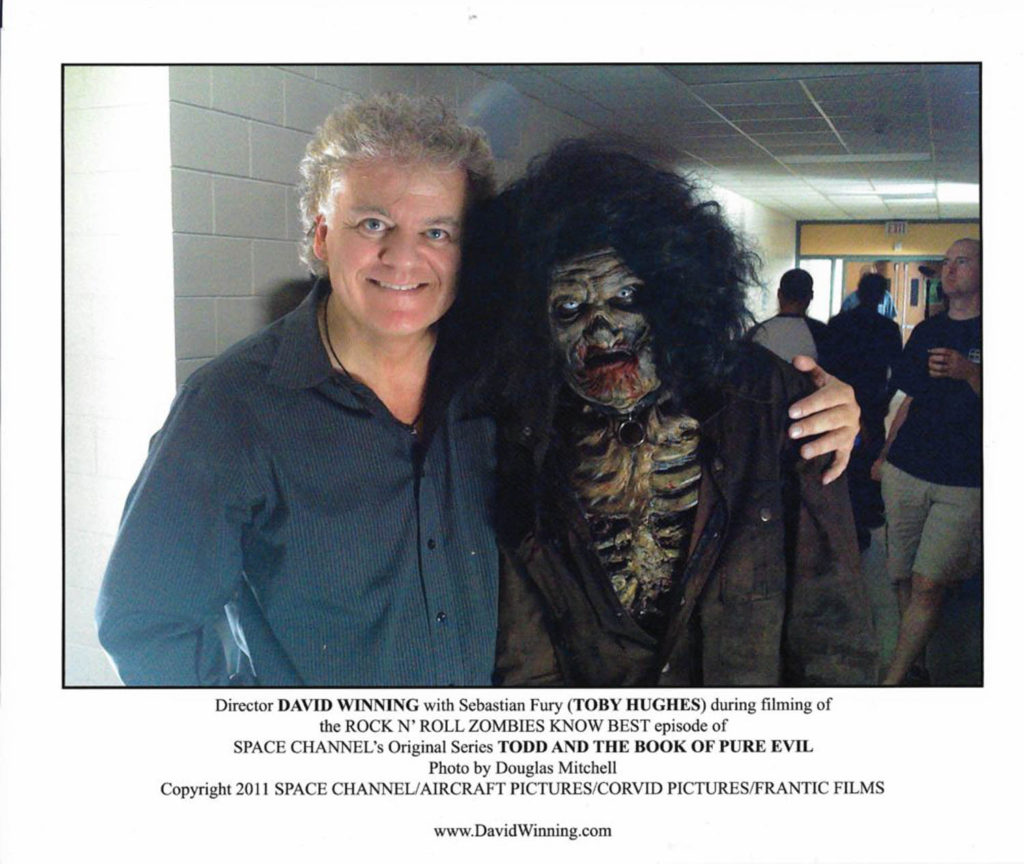

Let’s talk about another series of yours. Todd and the Book of Pure Evil. It’s about a group of high school students and this demonic book that unleashes all these horrendous things into their school, and they have a different adventure each week.

DAVID

You’ve seen those, right?

JAMES

I’ve seen most of that series. I’ve seen the episodes you’ve done. And it’s just one of those shows that pushes the boundaries. It’s wacky and fun and bizarre. What was the creation of that like?

DAVID

Well, it was completely politically incorrect. The guy behind that series is Craig David Wallace, who created the series as kind of a thesis project when he was at the Norman Jewison Film Center. It was his graduation project. So, they did a short film called Todd and the Book of Pure Evil which is their version of the pilot episode. And then they used the short film as the springboard to try to get the rest of the series made and Space Channel and some other companies got involved. And they ended up shooting it in Winnipeg of all places, covering various empty high schools with blood and all sorts of gruesome things.

And they wrote the first 13 episodes over seven years because they were trying to get them perfect. And I remember sitting down with Craig and he said, “Okay, we’ve got you,” and they had four directors, I think – and he said, “We want all the directors to read all the episodes.” So, I sat down, and I read the first 13 episodes, and I laughed. It was some of the best, funniest, most bizarre writing I’d ever read. And it’s a really weird combination of absolute gruesome horror and hysterical comedy and completely off base.

And when we got the green light and I went down and shot them and I had to shoot people saying some of the most horrible lines and I said to Craig, “Do you want an alternate on this line?” And Craig was, “No, absolutely not. It’s as written.” Because they were kind of like the Coen Brothers in a way. It was all so brilliantly written. And the wording was so biting and sharp and the descriptions and everything, he didn’t want any alternates. He didn’t want anything softened, and I realized that he was such a rebel kind of producer, that they wanted to go out and do exactly what they wanted to do and have everyone be so shocked that maybe it would be cancelled.

I thought, okay, that’s pretty bold, because you know, you’re never going to have a chance to come back and do this line, if you want to soften it and it was something just politically incorrect. But it was a very free series to do because nobody came out unscathed in that show. They made fun of everybody. And everything was just super violent, and I just had a blast making that show.

And then the weird thing that happened is it became a hit, and they went to Craig and said, “Okay, we’re going to do another season, so start writing some scripts.” And so, they didn’t really know what to do for the second season. The first season took seven years to write, and the second season took about three and a half months to write. It was a great series to work on; maybe the first season eclipsed the second season but the second season had a lot of really fun stuff in it and I had a blast working on it. Brave creative producers.

JAMES

You’ve worked on Earth Final Conflict, Andromeda, ABC’s Dinotopia, and you’ve done Stargate Atlantis, and I just wanted to touch on the Stargate Atlantis episode, you did called “Childhood’s End.” I watched it last year and again this week.

DAVID

That episode is one of my favorite things I’ve ever done. I was really proud of that episode.

JAMES

It had a lot of kids in it. It moves along really nice. And you mentioned Star Trek, and it has a little bit of the feeling of that episode of Star Trek, where the kids are growing up and they die when they reach puberty because of this disease. Remember that episode?

DAVID

It’s called “Miri.” With Kim Darby.

JAMES

It’s about a kid-based society.

DAVID

It’s funny you mentioned Star Trek, because when you work on those kind of shows and when you work on Andromeda with Kevin Sorbo, I go right back to being the kid watching the black and white TV in the basement. And I think, “Jeez, I’m actually here now. I’m creating this world. And even though I’m standing inside a fake spaceship, this is going to be so real for some 10-year-old somewhere in the world.”

And as people have told me, whenever you do anything, even if you’re not sure it’s going to be great, it always ends up being somebody’s favourite movie, or somebody’s favourite episode of the show. That’s what I take really seriously when I’m working on shows. Because I know it’s going to mean something to somebody and I can still tap into the 10-year-old in my head when I’m making these movies and try to see it from that perspective when I’m trying to tell the story.

And you know it was a great cast. And it was a really fascinating little story about these poor kids on this planet killing themselves at 25 because they think they can’t live to adulthood, because the Wraith will come and take them out. The kids were great. And you know we had a ton of fun, like, burying that little shuttlecraft that crashes in the opening sequences. It was a great episode to do and they had some really great directors on that show. Peter DeLuise was super nice to me and I just went in and I worked so hard to try to make this just a great episode. I’ve always been proud of that show and it won three international awards for directing. I’ve always been into the promotion factor of the career and I like to celebrate the work and hopefully people see it because you’re trying to keep the momentum of your career going.

JAMES

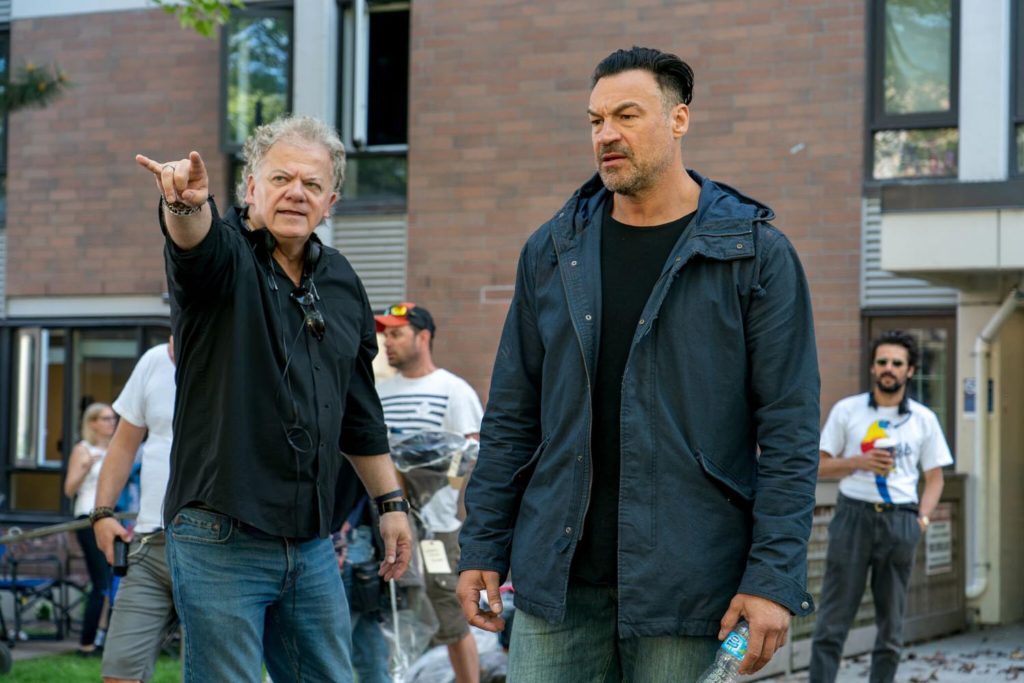

Let’s talk a little bit about Van Helsing and your involvement with that. I mean that’s a pretty bloody and effects rich show. How did that come about?

DAVID

Chad Oakes started out as a talent agent in Edmonton and then he moved down to Calgary and started Nomadic Pictures with Mike Frislev and they ended up hitting it big with Hell on Wheels, and in 2016 they asked me to direct Mutant World for them with Kim Coates and Amber Marshall for SyFy. That led to Chad getting Van Helsing and so SyFy and Netflix co-produced Van Helsing and they did the first season without me but then they called me second season and said, “We have a couple of episodes for you in a block.” And I said, “Great.”

So, I sat down and watched the whole first season. And the very first episode of Van Helsing is incredibly gory, and just blood splatter and violent. It had a little bit of that Tarantino visceral kind of punch to it that I just loved. And so, I ended up getting hooked on this thing and binge watched the entire first season. The first season’s amazing. It had a beautiful arc to the story, and there was a major change that happened in one of the characters in the series, about eight episodes in, that just completely knocked you off your chair and took the character in a whole different direction.

And when I got offered it, I said, “Can we do some Steadicam?” And they’re like, “Yeah, we’ve been waiting for somebody who knows how to use it properly.” So, I came in with an episode about cannibals called “Big Mama,” and if you get rid of all the politics and all the BS in the film business, you really end up being like a kid in a candy store. Because you get all these actors and these really cool scripts and this vampire apocalypse world that they created for you that’s brilliantly set-designed and you wake up sometimes and you think, “Was there an apocalypse, because this is so realistic.” And I’m just so proud of those episodes. I ended up doing six of them. I did two a season. And in the third season they called me and said, “We want you to do the finale.” Which, as you can imagine, is this golden position for a director. Everybody wants to do either the pilot or the finale where all the stories get wrapped up.

And if you said to me, that’s the only thing you get to do for the rest of your life, is this little weird vampire series, I would be thrilled because it was like playing cops and robbers when you’re a kid. You know, like chasing bad guys and stuff. And I just loved the whole good and evil battle with Van Helsing. It was so blunt and obvious. And with vampire characters you can do anything. And if you watch the series, they would take their favourite actors and they would make them not vampires for a few episodes, or the villains would become heroes and be humanized for a few episodes. It was just a blast. And it was a great cast to work with.

Aleks Paunovic played Julius and was amazing. And I ended up through a weird series of circumstances not working with the star Kelly Overton the first season I was there. She wasn’t in either of my two episodes. I didn’t end up working with her until the finale of the third season. So, she came to me and said, “I’ve heard a lot of good things about you. I liked your episodes but isn’t it weird that we haven’t even met until, you know, three seasons into this series.” She was great.

JAMES

So, since we’ve been talking about Van Helsing – lots of times you contrast your Van Helsing work with your Hallmark work – and you’ve directed other shows, I think that have a lot of heart, like Twice in a Lifetime, so it’s not something completely new. And you’ve done what? Twenty projects for Hallmark now?

DAVID

I’ve done 17 movies for Hallmark. Ten of them have been Christmas movies. Seven of them have been seasonal like summer/spring movies.

JAMES

I’ve got a list here: Marrying Father Christmas, Unleashing Mr. Darcy, Tulips in Spring, A December Bride, Falling for Vermont. And then you did as you mentioned Time for Us to Come Home for Christmas, which aired last December. Why do you think people have an appetite for these movies? And what draws you to the story as well?

DAVID

What draws me to them is just the challenge of making anything entertainment. I mean, anything you’re given. I mean, like I said with the killer bee show I started my television career with on Friday the 13th, I like being challenged to take stuff and make it better and elevate it. And with the Hallmark movies, it’s not as hard because it’s got a built-in audience and predictable storylines and people just love the comfort of that.

And I think in dark times, people just flock to Hallmark movies because there’s a comfort level and a feeling of safety and a security. And some of my best childhood memories were wrapped up in Christmas and that kind of magical fantasy feeling about, you know, the world loves each other, and everything’s great, and it’s all wonderful. That’s a beautiful feeling, and that really is Christmas when you’re a kid.

I think 85 million people watched these movies last year because there’s a huge need for safe entertainment in the world right now. Especially with so much upheaval going on politically and spiritually with people that I think people just want to pour themselves a glass of wine and sit down with some popcorn and watch these really safe wholesome stories because it has memories from their childhood.

JAMES

You recently directed Riddle Me Dead a Crossword Mystery for Hallmark, right?

DAVID

My 40th feature.

JAMES

So, what are the Crossword Mysteries and what is Riddle Me Dead about?

DAVID

What Hallmark smartly decided to do is they took their favourite stars like Candace Cameron Bure and Lacey Chabert and the people that they’ve done the Christmas movies with, and they started to develop spin-off mystery series with each of them. And so Lacey was doing Christmas movies and she wanted to branch off and do a mystery collection. So, the New York Times crossword puzzle editor, whose name is Will Shortz pitched an idea to Hallmark about doing a mystery series about a girl who basically does what he does – she creates crossword puzzles, but she also hooks up with a police detective and she ends up helping the police department solve murders.

And they’re lightweight mysteries. They’re not super violent, obviously, because it’s a Hallmark thing. They’ve done five of them now to great success and everybody loves Lacey. And the cop in the series is played by Brennan Elliott, who coincidentally went to my high school in Calgary but in the ’90s. And we’re shooting the first day and he said, “Well, I grew up in Calgary.” And I said, “What high school did you go to? And he said, “Aberhart, how about you?” And it was one of those weird moments where you kind of whittle it down and gradually realize that you’re neighbours. Anyway, so Brennan Elliott and Lacey Chabert started these movies and I directed number five, which premiered in April and it’s called Crosswords Mysteries: Riddle me Dead.

DAVID

And the plot is kind of fascinating. It’s about a game show. You know, all the scandals about the game shows in the ’50s. And people cheating on game shows. It’s kind of like that, and I can’t give too much of it away, but, Lane Edwards plays the game show host on this fictional game show called Riddle Me This and at the end of the first act he gets murdered on the set. And so Lacey Chabert has, of course, attended this taping and she gets embroiled in the whole mystery. And it was so much fun to do. We basically built a Jeopardy-like set inside a soundstage, complete with working cameras and I pulled things out of the script and moved them onto the game show set because I knew the stage was going to be fantastic. So much of what happens in the story actually ends up happening on the stage in you know, the dark hours.

It was a ton of fun and I’ve got a really good relationship with Lacey Chabert. I did a movie about seven years ago called The Tree That Saved Christmas with her. It was for Uptv and we shot it in eleven days and it ended up on the top five list of The New York Times for best Christmas movies of 2014. I don’t know how that happens, it’s like winning the lottery, right? So, I definitely advertise the fact that that happened, because I was really proud of it.

And Lacey’s famous to people from Mean Girls, and she was the little girl in Party of Five, the series. And The Tree that Saved Christmas kind of introduced her to Hallmark and now she’s done like 26 Hallmark movies. Mostly in Vancouver. So, when we did Time for Us to Come Home for Christmas together it was great to reunite with her and then while we were shooting she said, “Do you do mystery movies?” And I’m like, “I do everything. Vampires. Spaceships. Kid shows. What do you want?”

JAMES

Right, and so you did Crossword Mysteries, and you did the Christmas movie and you shot out in Vancouver with COVID protocols. How do you get a movie put together during COVID and keep it safe for everyone?

DAVID

This Saturday will be the first anniversary since the film business shut down. We called it Black Friday because the whole film business shut down on March 13. And slowly in July and August the industries in Vancouver, the IATSE Union and the Directors Guild and the various film production centers were trying to develop protocols as to how the heck are we going to get back to work?

And basically, film sets hired COVID departments. People that come in and are just specifically there to make sure that everyone is wearing masks. And we wear masks all day, obviously like anywhere else, but it’s still a hundred people working in very close proximity. Temperature checks are done every day. The actors on the show are tested for COVID once a week, or in some cases more than once a week, sometimes three times a week on some of the bigger shows. But as you can imagine, the worst thing to happen to the film business is something to slow down production because it’s just so hard to physically get these movies made.

And now we’ve got another whole element of safety and we have to just take everything even slower. So, it’s been a real learning curve. Obviously, the actors take the masks off just before they shoot and then pop them back on at the end and a lot of actors are wearing face shields. These kinds of plastic visors that come over their heads. And you know people are going around spritzing your hands all day long. And when you sign-in in the morning, when you arrive at set you have to go through a whole COVID protocol where you do a checklist, and they do the forehead temperature checks and everything and it’s really well regulated. One of the other things they’ve done is kind of divided into pods, you know. We get these wristbands when we go to work. And if you’re in the red zone, the hot zone, you’re in a small group of people that can be around the cast. And the extras, for example, are all separated from us and they come in at the last minute.

And I’m really proud of the fact that I’ve done three productions now with nobody getting sick. But I will say that I felt kind of guilty in some ways getting back to work when so many other people are struggling. I think things are starting to fire back up, but, I mean, I feel for the restaurant industries and all the companies that have shut down and closed. But I think the film business is one of the safer businesses right now, just because you can’t afford to get someone sick, it’s just such bad publicity and obviously you don’t want people ill for any reason. So, I have been proud of the fact that we’ve been able to keep people safe.

JAMES

So, you mentioned Riddle Me Dead and Time for Us to Come Home for Christmas and Lacey Chabert and I know I read some other interviews with her and she’s not the only one, but a lot of actors talk about how much they like to work with you, and they enjoy your approach on set. I wonder what type of work and creative experience do you try to create for the cast and crew?

DAVID

When I started out, I used to work as a PA for Access TV and I used to get yelled at by directors and they used to do a lot of screaming and had tempers. And I thought, “I don’t know if I want to be in this business if this is the way it’s going to be.” I worked for a lot of hotheads when I started out in my early twenties and so I thought, “If I was doing this job I’m going to treat people better.” And I always think people do their best work when they’re relaxed and happy and my parents ingrained in me that you have to create a world where people are happy.

And so I’ve spent a lot of time trying to be a party host when making movies because I have never lost that childhood love of movies. People I work with say, “You seem so excited making this that I got reinvigorated working with you.” Which is kind of why I’m there. I’m supposed to be a cheerleader. And I’m supposed to try to remind people about why they’re in the business. Because a lot of people forget. It’s got to be more than a paycheck. So, I think if I have a good reputation, it’s because I try to make people as relaxed and to let them have as much fun as possible. And I have great respect for actors. I love working with actors. It’s hard enough just physically getting movies to happen so why not try to make it as comfortable an experience for people as possible.

Fay Winning and David Winning

JAMES

What does an actor need most from his director?

DAVID

They need to feel safe. And I end up becoming the only critic that matters for their performance. It’s just the actor and me. You know, like Lacey and I have a great relationship. You work with people who trust you. And it’s about trying to guide their performance and trying to elevate the material because if they look good – I look good.

So, I’m always trying to make people feel like they have the best playground to work in. And then what’s always fun, a lot of times, even in comedies I always try to do a third take where you let people just do whatever they want to do. And you’d be surprised how often that material ends up in the show. When I was doing Breaker High years ago for Saban, Ryan Gosling, who went on to some success, and Tyler Labine used to be just hysterical together. They were playing the two kids and we would always do what we called a Jimmy and Sean take where we would just let them go and do whatever they wanted and some of the funniest moments from Breaker High were because you created a comfortable enough place so that people could spread their wings and just experiment.

And I don’t know if you’ve been on set in a while but because of the nature of the digital stuff, you don’t usually cut. You’ll shoot a scene and I do it all the time – still rolling – still rolling – still rolling – take it back, take it back, let’s try it again. And I’ll direct live you know. Just try it with this and try it with that and you don’t get this rigid “Cut” and the scene is over. You just keep rolling. Sometimes you do three or four takes without ever cutting the camera. Or you can drag cameras around and reposition stuff while we’re rolling because you have the freedom to do that. Because it’s digital. It’s not like back in the STORM days, I mentioned earlier, where you’re on a three to one shooting ratio, and I only have so much film. Then everything had to be very specific and perfect. But there’s so much more freedom now with the digital technology.

JAMES

Well maybe talk a little bit about that 40-year career what are some of the big changes you’ve seen over that span of time?

DAVID

Well, actually, I’m proud of the fact that I worked on the very first high-definition television series in the late ’90s. For a long time people used to say, ER, you know the George Clooney TV series, was the first series to shoot HD digital, but actually Earth Final Conflict was the very first series that used Sony 900 cameras and was exploring this whole technology and all the cameras were cabled up. There were cables everywhere. And now of course, it’s completely freeform, which is great. But I was very proud of the fact that I was really in on the ground floor when digital came along.

I miss film because when you used to shoot film, even on a TV show like Andromeda, there’s a comfort to sitting beside the camera and hearing the film churning through the magazine. That was the old days and we’re making movies, you know. But now it’s all so electronic. It’s all “ones” and “zeros”. “Stand by for data capture!”

I remember having my whole world kind of rocked years ago when I went to a Pantages Theatre in Los Angeles which was a designated testing ground for George Lucas’s 8k projection systems and I remember going and watching some digital stuff that had been shot at night on a 4k system and then projected in 8k, and I thought, “Film’s dead.” And in the last ten to fifteen years incredible strides have been made in digital photography and I realized, “Oh, you won’t have to ship film prints to theatres all over the country anymore. Now it’s just a little HD drive and eventually they’ll just be beaming the signal out from some central location to all the theatres.”

JAMES

And boy, did it happen fast. And you’re right you don’t have to do prints and you know 40 years ago even with a big film, they might only make 100 or 200 prints. And it starts in New York and LA and it goes to the A markets and then it goes to the B markets and like you say, it could be six months to a year before it gets to a theatre in Calgary because they only have so many prints. And then the funny thing is the print arrives in Calgary after it’s been on the road for a year and then the projection you see is full of scratches. And it might even have a film splice in it. It was such a totally different experience. We forget because what we see now is so clean.

DAVID

And to connect back to something we talked about earlier. That’s why John Carpenter’s career happened. It happened because Halloween was released city by city by city. And it started to do this gradual build. It was released in October in LA and into small little markets. And it was brushed off as a little shocker movie and then it eventually worked its way to New York, and he got a Village Voice review, where it basically compared him to Alfred Hitchcock, “This is incredible suspense.” And then his career exploded. But that kind of thing doesn’t happen anymore, where you get this kind of slow-release. In the old days, somebody would just take a print and drive it around the country and rent a theatre and show it in all these little markets and try to build up interest all over the country. That’s just not a concept that occurs anymore. Nowadays, you get Netflix dropping an entire series in one day.

JAMES

So you’ve had a career that has lasted 40 years. It’s a tough business. You grew up in Calgary so you’re used to the boom and bust cycle because Alberta’s economy is oil and gas, and film and television is very much boom and bust for a lot of artists. So, I’m just curious, what strategies have you used in your career to help you ride the ups and downs working in the film and television biz.

DAVID

I’ve been on a good run for the last four or five years. I don’t want to jinx it but Hallmark Channel has been very good to me, obviously, and with the Van Helsing stuff it’s been a pretty steady run. I’ve spent probably all of my 40 years being like a promo guy. You know, I’m just trying to promote stuff and I always thought that you’d eventually get to a stage where you wouldn’t have to do this anymore. You just arrive, and you’d be the famous director and people just hand you your projects. That just doesn’t happen. And it doesn’t happen more now than it ever did in the past because there’s so much product, and there are so many channels and potential places for things to be produced.

You know, when we were growing up, it was three networks, and then it became three networks and Super Channel, and then it became satellite channels and now there’s 400 channels that need product to fill them. So, I don’t know how you don’t get lost in the mix. I just think I’ve been really lucky. I’ve always been sustained by an existing industry and I got the reputation of being kind of like a go-to guy. I can’t tell you how many shows I’ve taken over where the director has been either fired or got sick or got COVID or something happened and they fly me in. They call me on the Sunday and fly me in on the Monday and we start shooting, and I’m walking onto set reading the script and going, “Okay, you’re married to who? And you’re going to kill him in this scene.” I’ve done that a million times.

And that’s part of the reason it’s so much fun. I’ve done work on 29 different television series. And television is completely about the clock. They don’t care who you are or who the director is and film is the same way. “This movie has to happen today, in this amount of time, and if you don’t do it, there’ll be somebody different here tomorrow that’ll do it.”

One of my things I’m most proud of is that I’m incredibly prepped on the shows I direct, like you direct them in your head a million times before you ever get close to the actors or the sets. And so you can see all the shortcuts in advance. We could do this together and combine this scene and do this and that. And television taught me to have this incredible eye on the clock all the time, right. So, I always know where we are in the day and the first ADs are coming to you and saying, “You only have so much time.” I know exactly where we are in the day. I know exactly how much time I have. I know what tricks I’m going to pull out at the last minute to finish this undoable day. Because in television, you’re shooting 12-page days. It’s just ridiculous. The pace is ridiculous. But I think because I’ve faced all of the scary stuff I feel more relaxed directing now because I don’t get surprised by too much. I know how to fix things when things go wrong.

And I’ve always felt like I still maintain the excitement about trying to make everything different and exciting, but I’ve definitely had ups and downs. I remember very clearly 2008/2009 when the bottom kind of fell out of the industry and they stopped making TV movies, and I didn’t work for two and a half years. Not one booking in two and a half years. And I had come off a fairly steady bit of work so I had you know some money backed up but I started selling property and I have no nest egg left and I honestly thought, “I guess I’m retired. I guess that was it.” I’ve had a couple of little plateaus like that. You just never know where the next job is coming from. I have no idea what I’m doing next week. I could get a call today and be in Budapest the following week.

JAMES

You mentioned World Fest Houston and you’ve had a chance to go to some conventions and do some panels and things like that and I’m just curious, what’s it like to go and be a part of that and talk to the fans from the shows?

DAVID

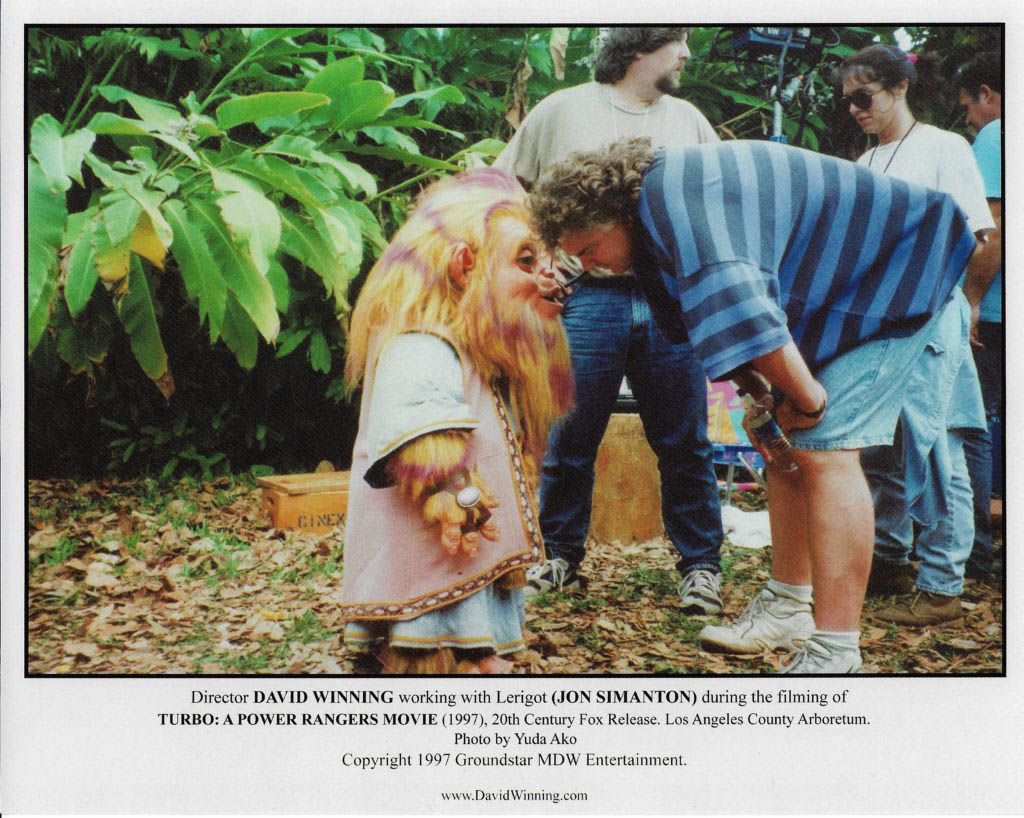

I love doing that. I used to do it a lot when I was doing Andromeda and Stargate: Atlantis I went all over the states to all these little science fiction conventions, and they asked you to come and sign things and so you take a whole bunch of pictures of you working on different shows with various people and the science fiction fans are the best. In Springfield, Missouri, years back, this guy rolled up to me in a wheelchair, and he was in a full Klingon outfit. And I said, “Hey, how are ya?” And he would only speak in Klingon. Sci-fi fans are so much fun. And I’ve done Comic-Con San Diego a couple of times, with 130,000 people, which has been very bizarre. Sometimes nobody comes and talks to you because nobody knows who the directors are but, when they see you have a connection to various science fiction shows they feel like they know you. And there’s a lot of seven-year-old Power Ranger fans in the world that think I’m a superstar because I directed the Turbo: A Power Rangers Movie sequel in ’97 some 25 years ago. I still get invited to the MorphiCons in Pasadena every year.

JAMES

It’s fantasy time Dave. So, what television series from the past would you go back in time and take a shot at directing and why?

DAVID

Star Trek. The original series. I have fantasized for years about going back in time and being on that set. I would love to have done that. I would have loved to have directed 24. I loved 24. It was one of my favourite action series. I would love to have directed some of the Night Gallery episodes or Twilight Zone even back in the ’60s you know. But probably Star Trek TOS would be the thing I’d go back to direct. I’ve walked around stage 31 at Paramount in Hollywood and had exactly this thought many times. It was the original Desilu Studios Stage 9 until they merged with Paramount in 1967. This soundstage housed all the sets that represented the interior of the Enterprise. Hung out there while they were shooting Ted Danson’s sitcom Becker.

JAMES

You’ve done a lot of interviews over the years and I’m wondering is there anything that you would like to talk about that you just don’t get asked? You know, any subject, any stories, anything that you go gee I wish they’d asked me about that?

DAVID

You know, I always like to come back to my parents and the fact that I was so lucky I got the parents I had because, you know, I was adopted. I really wish my Dad was able to have seen more of my career, because as we talked about he stayed supportive even when he didn’t really understand it because he knew it was making me happy. So, I always try to honour my parents. And the temperament that I have is really completely from them. I was nurtured in a very supportive environment when I grew up. And I love the fact that that extends into whatever I do as a career in entertainment and the fact that I have a reputation for being a good guy to work with. And I’m proud of that and I think my Dad would be proud of that if he knew about it.

And sure, the hair gets gray, and you get older, but inside, I’m still this 15-year-old kid making movies in the backyard. And I never want to get rid of that, and the thing I don’t say enough is how incredibly lucky I’ve been to have survived 40 plus years in a business where people just drop out. I’ve been incredibly lucky. I would love for you to put that in because that’s what I feel is the thing that I never get to say, because I was lucky to land with the parents I landed with and you know, obviously I’ve worked very hard, but I’m just very lucky to have been able to sustain a 40-year career because if you knew the politics I’ve had to negotiate and all the competition that’s whizzing by me you’d be surprised that I’m still standing upright making movies.

And people think, “Did you design this career?” No, I wanted to pay the rent. I just wanted to keep working. So, I’m happy that they still call me. I go where the work is. I’ve never turned down a job. I’ve done 17 movies for the Hallmark Channel, but I have no idea what I’m doing six months from now. That’s the way it is. People think, “Oh, he must have it all set out so he does four a year and you start this one and then you prep the next one and then this month you have a little vacation, and it’s never been like that. I just wait for the phone to ring every Monday and most Mondays it doesn’t ring.

David’s mother and biggest fan sadly passed away at 98, weeks after this interview was conducted. She was integral to instilling in him the love of family, sensitivity and humility, and wholesome values that allowed him to flourish in the Hallmark universe. She was a gentle, kind, caring soul and will be missed. The Hallmark Channel in Los Angeles made a large donation in her honour to one of her favourite charities.