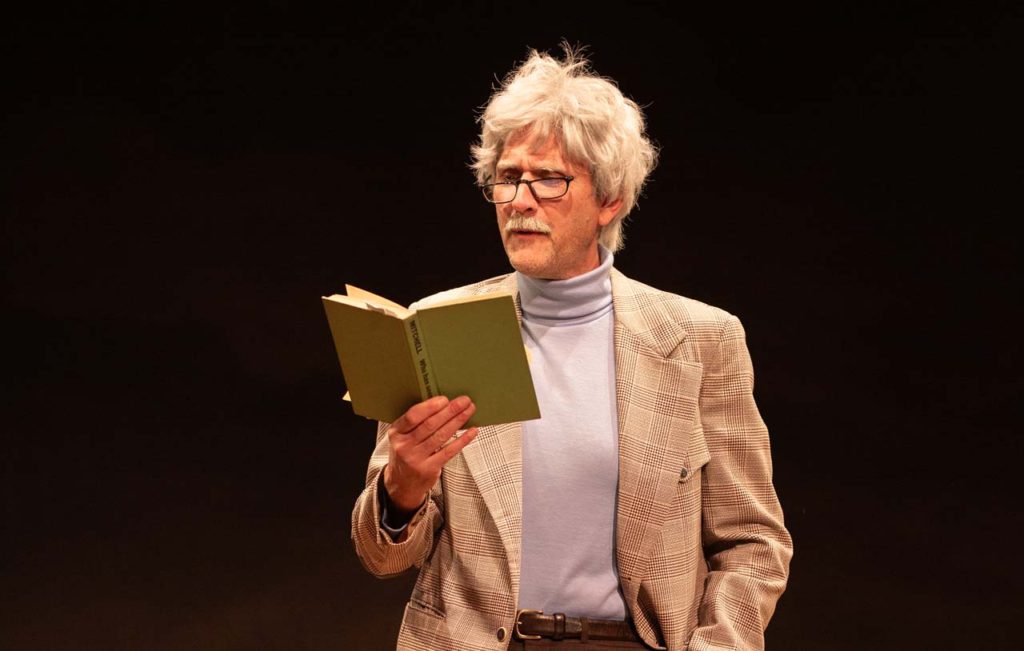

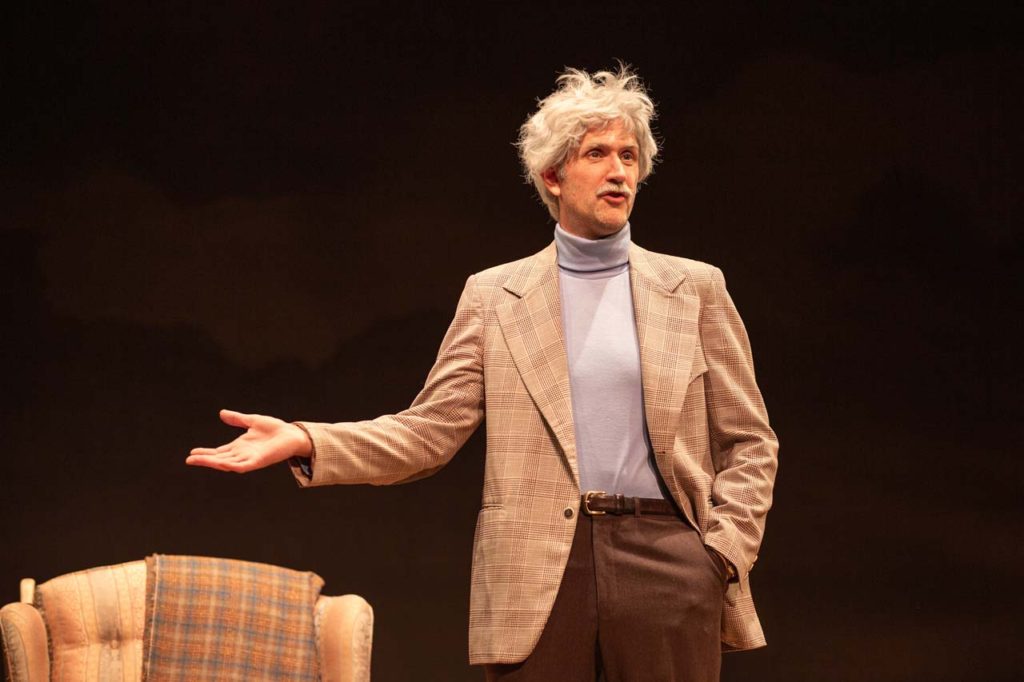

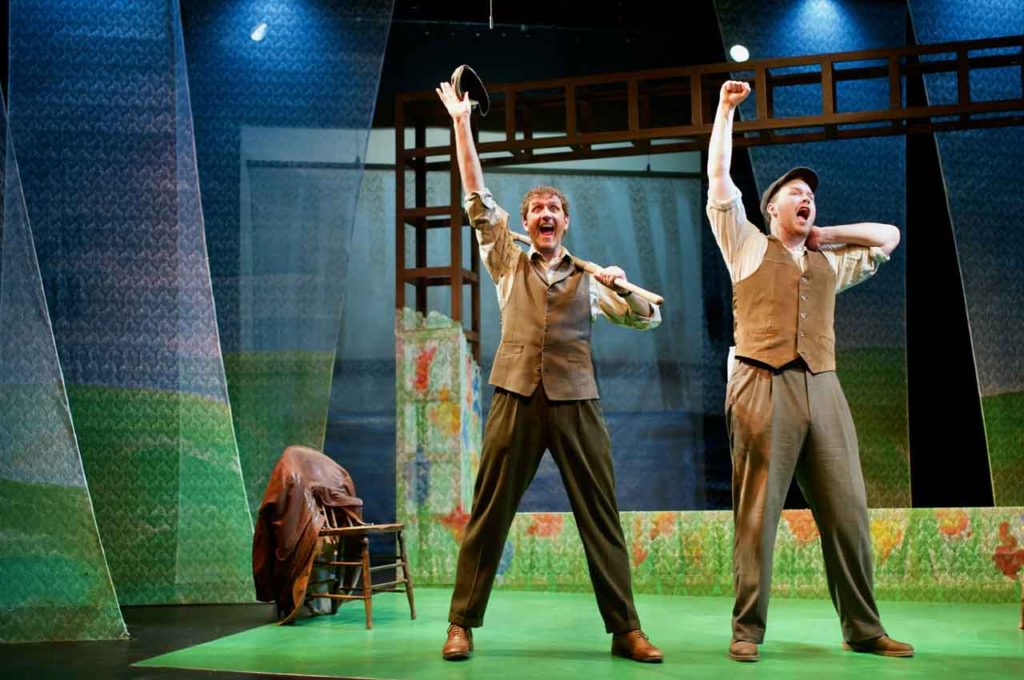

Magic Lies: An Evening with W.O. Mitchell is a joyful, fun, and feel-good night at the theatre all brought to life on the Rosebud Theatre’s Opera House stage in a brilliant performance by Nathan Schmidt.

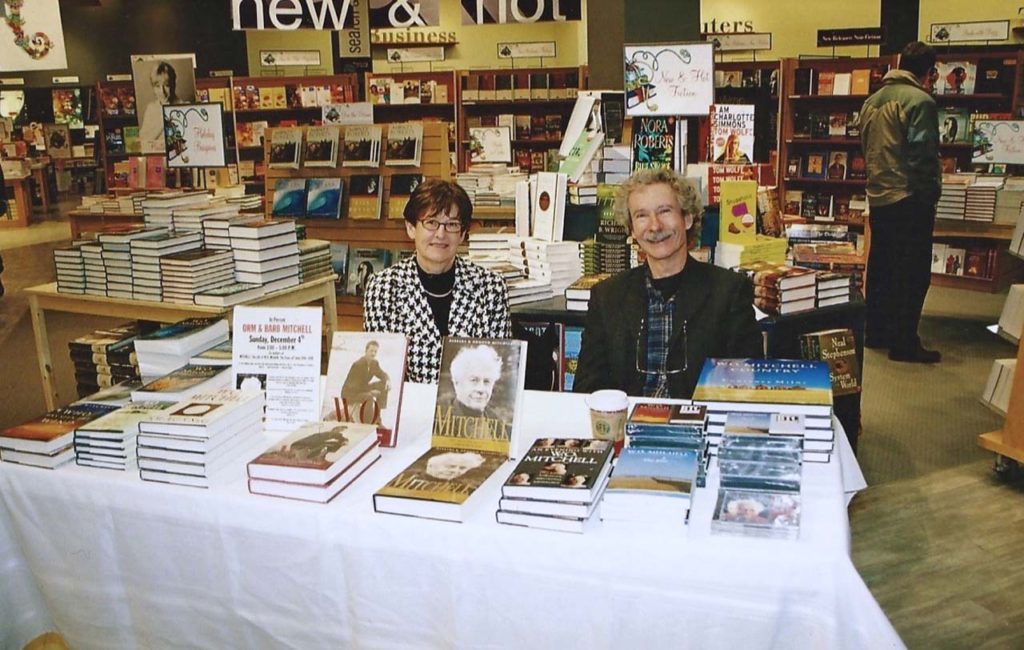

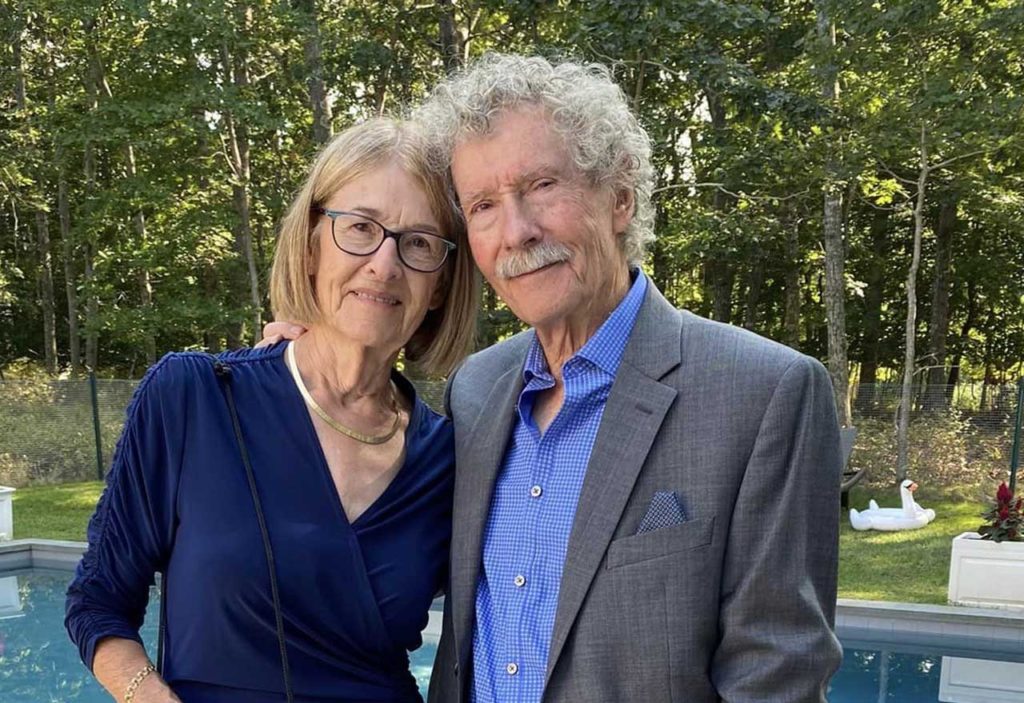

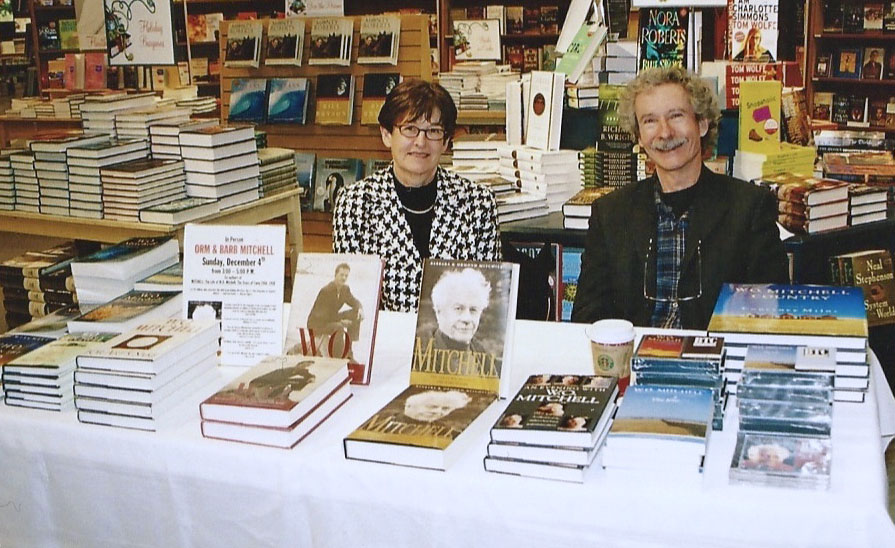

Based on the works of W.O. Mitchell and penned by his son and daughter-in-law, Orm Mitchell and his wife Barbara, the play weaves together an entertaining and insightful script that travels between Mitchell’s fiction and the story of his life.

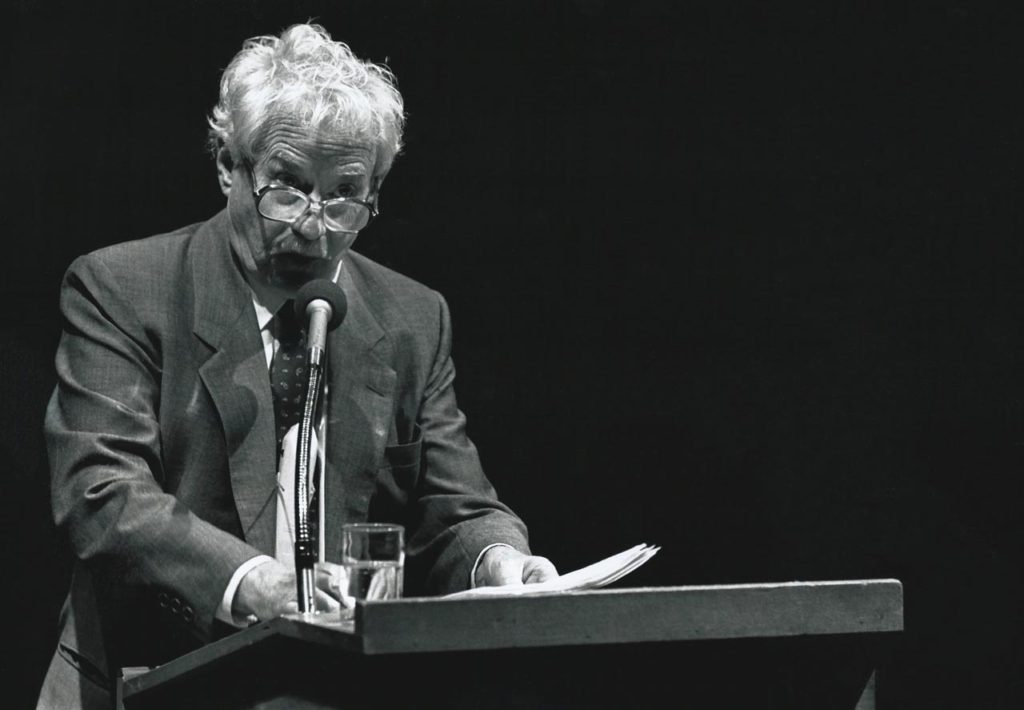

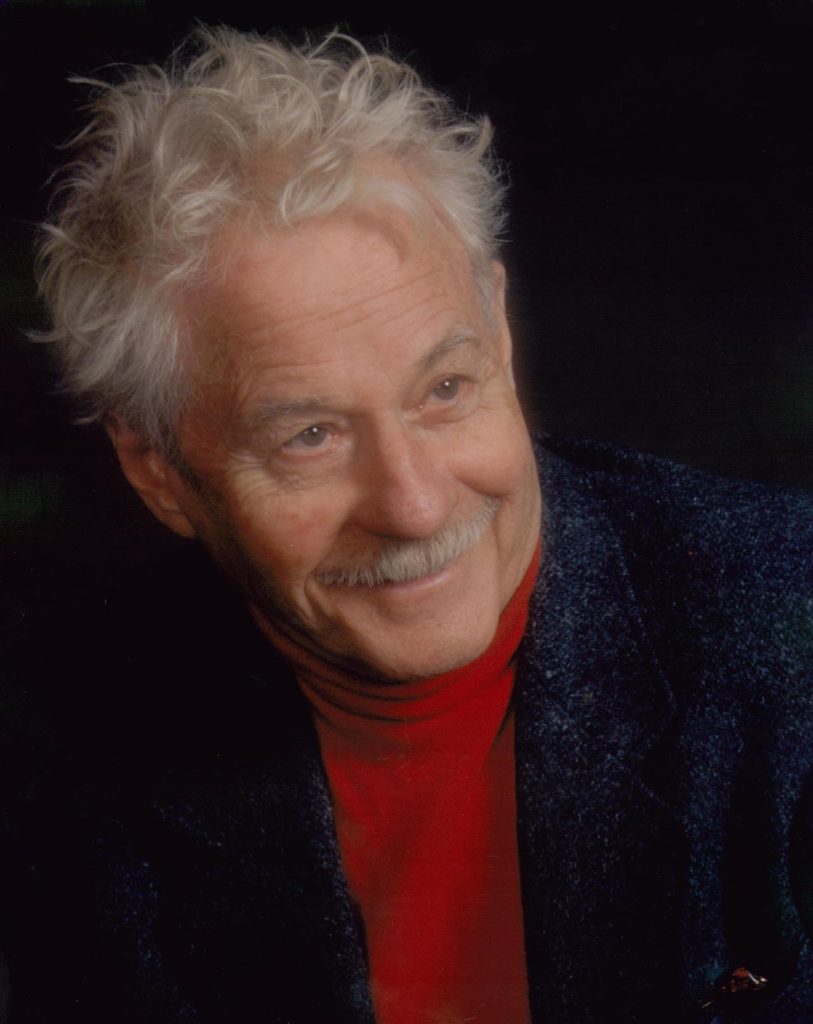

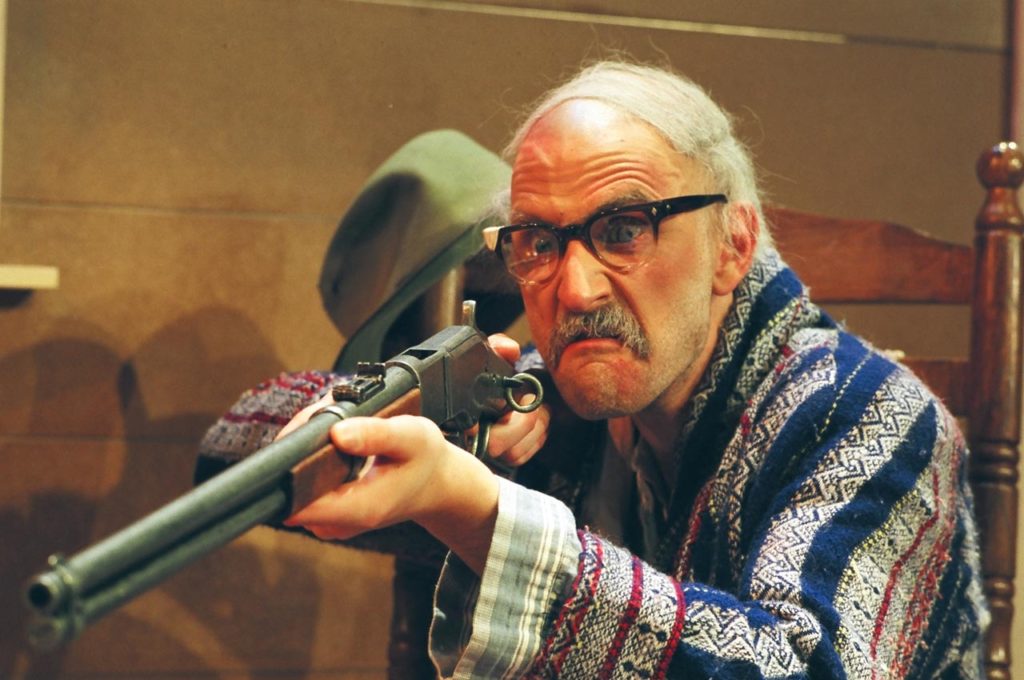

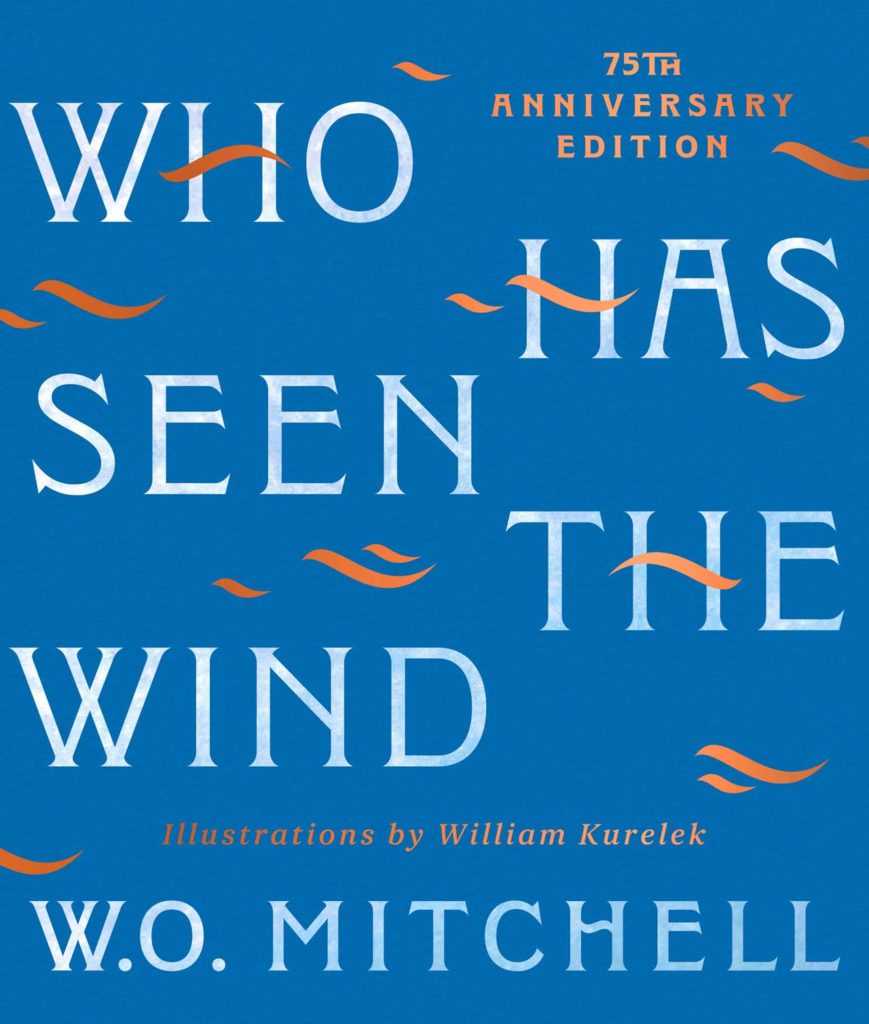

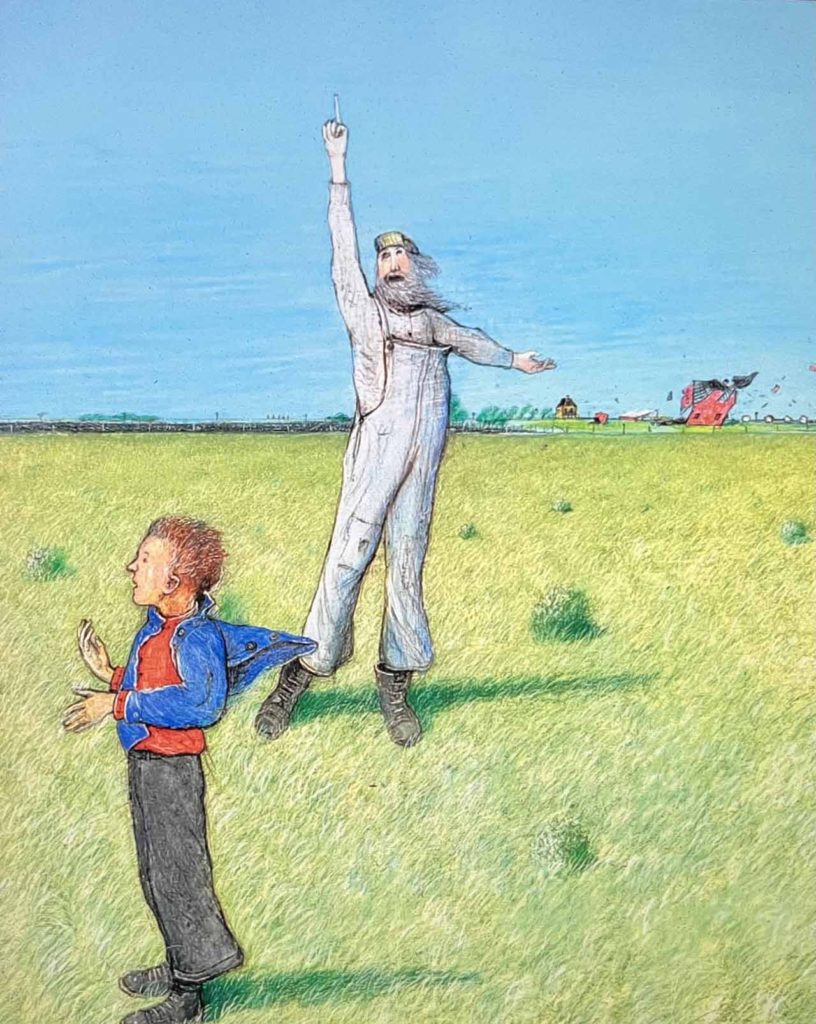

Mitchell was a writer, performer, and teacher who is best known for his 1947 novel Who Has Seen the Wind. The novel beautifully captures small-town life and the world as seen through the eyes of a young Brian O’Connal growing up on the Saskatchewan prairie. Mitchell is also known for his Jake and the Kid stories which were popular radio plays during the 1950s. No stranger to the stage himself W.O. Mitchell was a storyteller who performed his one-man shows across Canada and penned several plays for the stage including The Kite, The Devil’s Instrument, and The Black Bonspiel of Wullie MacCrimmon.

I contacted Nathan Schmidt to talk with him about the production and the challenges of performing a one-man show. You can read that interview by following the link above. I also spoke with Orm Mitchell to talk with him about his father’s work and the journey Magic Lies: An Evening with W.O. Mitchell took to reach the stage.

JAMES HUTCHISON

Orm, every literary work takes a journey from idea to finished work. Tell me a little bit about the journey that Magic Lies: An Evening with W.O. Mitchell took to reach the stage.

ORM MITCHELL

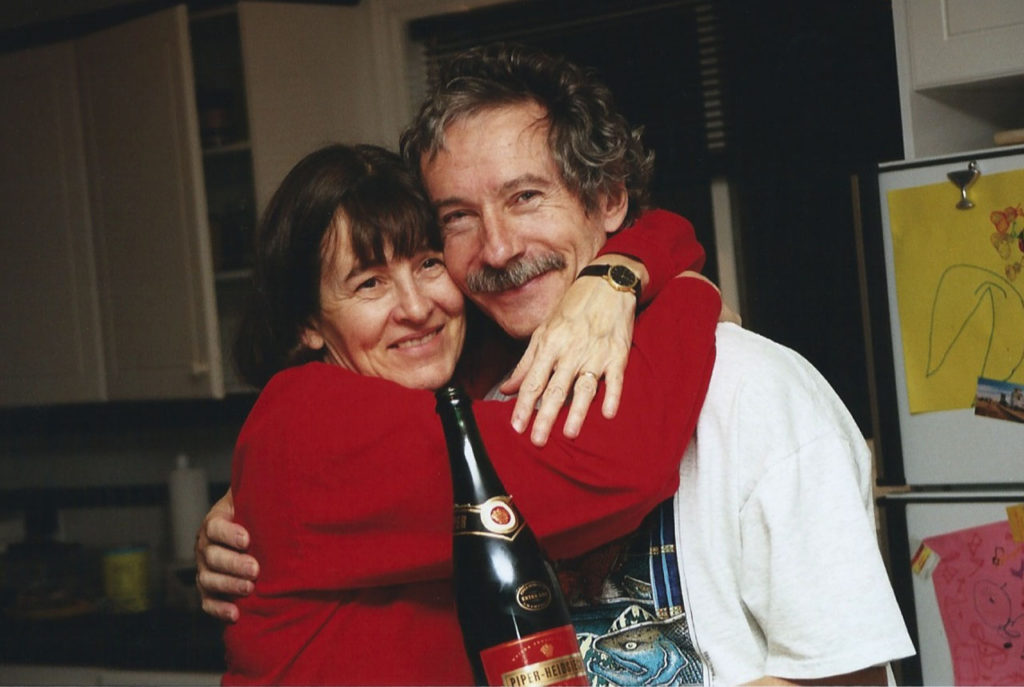

Well, it’s a journey that took close to twenty-six years. My father had prostate cancer so his last three or four years were not pleasant. He was in a hospital bed in the family room on the first floor of the house in Calgary and he was withdrawing more and more. And Barb and I wanted to keep him engaged. So, we suggested, why don’t you do a collection of your performance pieces that you’ve done over the years in your one-man shows? And he loved the idea. So that came together in a book called An Evening with W. O. Mitchell.

And as soon as that came out, two people came to us who wanted to use that book and turn some of the pieces into a one-man stage show, but Eric Peterson who they wanted to do the piece said he felt uneasy about doing this while a living author is still around and especially an author who has really put his distinctive stamp on the pieces.

There were other people who came to us over the years, and we were always in the role of acting as script consultants. And it never really got off the ground. So about 2008, Barb and I decided we’re going to write this ourselves. We did a really thorough rewrite and we sent it out to Theater Calgary and a few other places, but no one bit. So, we put it in a drawer and forgot about it.

Then during COVID, we realized that theatres were going through a very rough time. They couldn’t have an audience. There was no money coming in. And we’ve been really fond of Rosebud Theatre because they’ve produced W.O. Mitchell’s plays. They did Jake and the Kid, and they did The Kite twice, and we’d heard how wonderful Nathan Schmidt was playing Daddy Sherry in The Kite.

And so, I wrote to Morris Ertman the artistic director of Rosebud and said, “Look, Barb and I were thinking of making a donation to you guys because we know all theatres are struggling and we came up with what might be a better idea. Why don’t you do this one-man show and use Nathan Schmidt because we hear he’s been wonderful. And it’s inexpensive. It’s one person. You can stream it. And you might be able to get some income from streaming it during the COVID years.”

And I never heard back from Morris until about a year ago, July. And he said, “Orm, could you send me that script? I seem to have lost it.” And so, I sent it to him, and we saw him last November and he said, “I have decided to do this show and to use Nathan Schmidt.” It was close to twenty-six years from when the idea first came up to finally getting it on the stage.

JAMES

You call the play Magic Lies: An Evening with W.O. Mitchell and I’m curious about the choice of title. Why did you choose Magic Lies? What’s the significance behind that?

ORM

That’s one of his favourite phrases. And he always used to say when people asked him about his creative process and his stories that every bit is the truth. What he meant by that was that he was a very observant watcher of the world, and he would pick up bits and pieces of people or details of landscape.

And I remember he used to tell his writers in his writing groups that you have to draw on your own autobiographical experience and find images, bits and pieces of sensuous detail, and you have to appeal to your reader’s sense of smell, taste, and touch. You’ve got to make them see something that you are describing. You’ve got to make your reader smell what it is that you are describing. All of those sensuous details that he collects and puts together to form and create that illusion of reality draw the reader into the story. So, every bit is the truth, but the whole thing is a lie. A magic lie. It’s a magic lie because it’s the catalyst that helps a reader explore consciously and unconsciously various universal human truths.

JAMES

What do you think your father’s reactions and musings would be if he was able to see himself portrayed on stage?

ORM

My father was a master at timing, and he really admired an actor who had that sense of timing. You know someone who pauses in the right places and lets the audience into the story with those pauses. He was once told by someone when he was doing an acting role, “Bill, you’re overdoing it. It’s like an orange. Don’t squeeze all the juice out of the orange. Leave some there for the audience.” It’s a lovely metaphor for an actor who knows not to overdo it. And Nathan was just so good at that, and my father would have admired that.

JAMES

It takes a lot of discipline to put in the pause.

ORM

It’s a wonderful storytelling technique. And Nathan did this beautifully. In the story in which the boys blow up Melvin’s Grandpa in the back house when the dynamite goes off Nathan as W. O. stops and looks at the audience and takes out his snuffbox and he takes a piece of snuff and the audience is hanging there. Okay, the dynamite has gone off. The old man is in the back house. What happens next? And it is a lovely long pause, and then Nathan as W.O. looks at the audience and says, “Let me tell you something about dynamite.” And the audience just loved it.

The other thing my father would have admired was Nathan the actor has to make the role his own. He can’t just mimic my father. He uses bits and pieces of W.O. but at the same time the storytelling if it’s going to be effective – if it’s really going to zing with the audience – Nathan has to make it his own. By opening night he had made it his own and as the show goes on that role will more and more become his, and I think my father would have recognized that and would have admired that very much.

JAMES

Let’s talk a little bit about Who Has Seen the Wind your father’s best-known work. It was published in 1947 and was an immediate success. And at the time the Montreal Gazette said, “When a star is born in any field of Canadian fiction it is an exciting event…Here in this deeply moving story of a Western Canadian boy, his folk and his country, emerges a writer whose insight, humanity and technical skill have given the simple elements of birth and death, of the inconspicuous lives of common man etched against the bleak western landscape, the imprint of significance and value.” Why do you think this book and this story resonate so deeply with its readers?

ORM

Here you have a book that is set in the prairies during the dirty thirties. It’s very specific. One of the things that critics in Canada used to say was, “Who cares about Canada? Who cares about a story where Bill and Molly meet in Winnipeg and fall in love?” W.O. was one of the first, if not the first writer, to put the Saskatchewan Prairie and the Alberta foothills on the literary map.

But then the corollary to that is you want people whether they are in London England, or Australia, or China or wherever they are to read that story, and you want that story to come alive for them. It’s what Alistair MacLeod used to say, “When you write your stories about a specific place and characters you want to make them travel.” I love that line. You want to make them travel. Who Has Seen the Wind sure as hell travelled. It has been translated into Chinese. And it has been translated into South Korean. It has sold over a million copies in Canada, and I think it will continue to travel.

One of the reasons why I think it travelled is that my father was wonderful in understanding the child’s world. He was really good with kids, and he managed in Who Has Seen the Wind to get inside the head of a kid in a way that has rarely been done. He manages to dramatize how Brian a four – five – six – seven – up to eleven-year-old looks at the world – and that’s universal. He managed to create characters and in particular Brian looking at the world in a way that resonates with readers all over the world.

JAMES

So, I got the 75th-anniversary edition of Who Has Seen the Wind out of the Calgary library and it’s a very beautiful book. It came out last year. Has beautiful illustrations. The typeset. The cover. The paper that you use. It’s really just a work of art. And I came across a passage early in the book where he’s describing Brian lying in his bed trying to fall asleep.

“For a long time he had lain listening to the night noises that stole out of the dark to him. Distant he had heard the sound of grown up voices casual in the silence, welling up to almost spilling over, then subsiding. The cuckoo clock had poked the stillness nine times; the house cracked its knuckles, the night wind stirring through the leaves of the poplar just outside his room on the third floor strengthening in its intensity until it was wild at his screen.”

And that’s just beautiful and that reminded me of my own childhood and being in bed listening to the sounds of the house before falling asleep, and I know this is probably an impossible task, but do you have a favourite passage? Is there a passage you could select from your father’s writing that is for you perfect?

ORM

There are so many. I was thinking about Who Has Seen the Wind and the last three pages of Who Has Seen the Wind – is a wonderful prose poem. And in fact, when he was writing that he had his Bible open at Ecclesiastes and he was trying to catch the rhythms and pauses and repetitions of Ecclesiastics. It’s a very significant passage for me because I can remember standing in the High River Cemetery when we buried my father and that was the passage that I read from as part of our family ceremony.

But there’s one passage from How I Spent My Summer Holidays which is kind of a companion novel to Who Has Seen the Wind. You can imagine Brian, now grown up and going into adolescence. How I Spent My Summer Holidays at the human level is a much darker book than Who Has Seen the Wind. But there’s a scene right at the beginning where Hugh the narrator, who’s in his 70s, has gone back to his prairie town roots and he says,

“As I walked from Government Road toward the Little Souris, the wind and the grasshoppers and the very smell of the prairie itself – grass cured under the August Sun, with the subtle menthol of sage – worked nostalgic magic on me. These were the same bannering gophers suddenly stopping up into tent-pegs, the same stilting killdeer dragging her wing ahead of me to lure me away from her young; this was the same sun fierce on my vulnerable and mortal head. Now and as a child I walked out here to ultimate emptiness, and gazed to no sight destination at all. Here was the melodramatic part of the earth’s skin that had stained me during my litmus years, fixing my inner and outer perspective, dictating the terms of the fragile identity contract I would have with my self for the rest of my life.”

And I just love that prose that is so rich in detail. And my sense of the three most significant novels that he wrote are Who Has Seen the Wind his first novel, The Vanishing Point, and How I Spent My Summer Holidays. Those are books that will last, I think.

JAMES

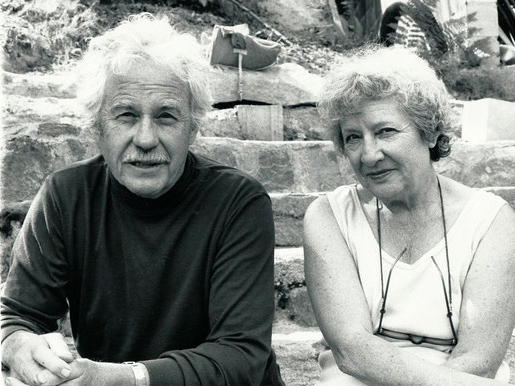

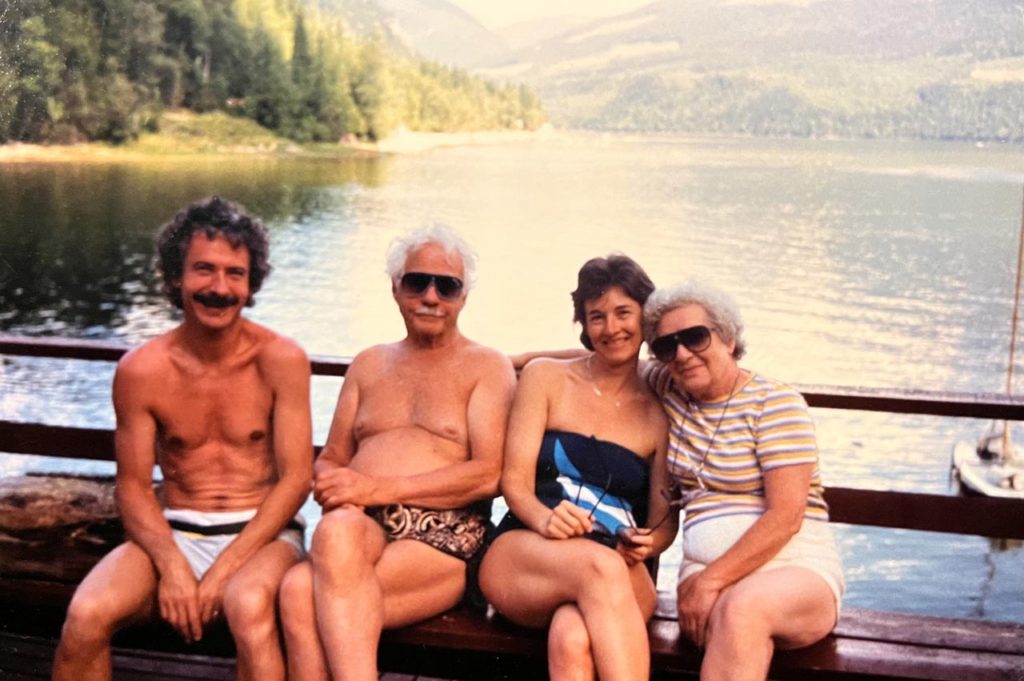

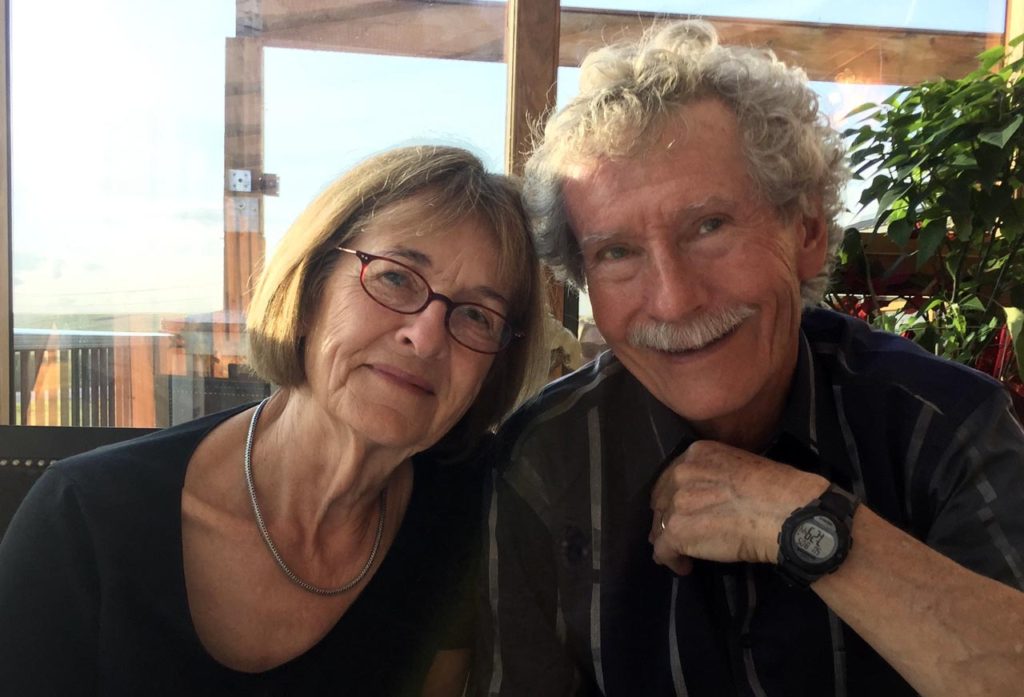

I know it’s hard to sum up the life of a man in a short interview, after all, you and Barb have written a two-volume biography about your father. But how would you describe your father, the writer, the public person? And then how would you describe W.O. Mitchell, the man – your father?

ORM

The main thing he wanted to write was a story set in the real world and to create characters that interact in a very realistic way in order to explore larger human truths. But he wasn’t just a writer who typed stories that would appear in print. He also was an oral storyteller, and he gave his one-man shows – and he always used to call them one-man shows – because he didn’t give the usual literary readings where someone is introduced and then he reads a passage and takes questions from the audience. He gave one-man shows where he went on stage and he performed. And even something like his Jake and the Kid series on CBC – those are oral narratives. He really drew on the oral storytelling traditions of Western Canada.

And I suppose that’s one of the reasons why both Barb and I have this feeling – not an obligation – but this feeling that we want to continue that legacy of my father’s writing, but also both Barb and I were very moved on opening night because we felt we had achieved the goal of continuing his legacy as a storyteller on the stage as well.

As a private person, as a father, he really knew the child’s world. Not only did he know how to write about children, but he also knew how to react with them, and how to interact with them. And my brother Hugh and my sister Willa and I were blessed with a father who was sympathetic and who knew that child’s world, and he played with us, and he was really a wonderful parent to have and to grow up with.