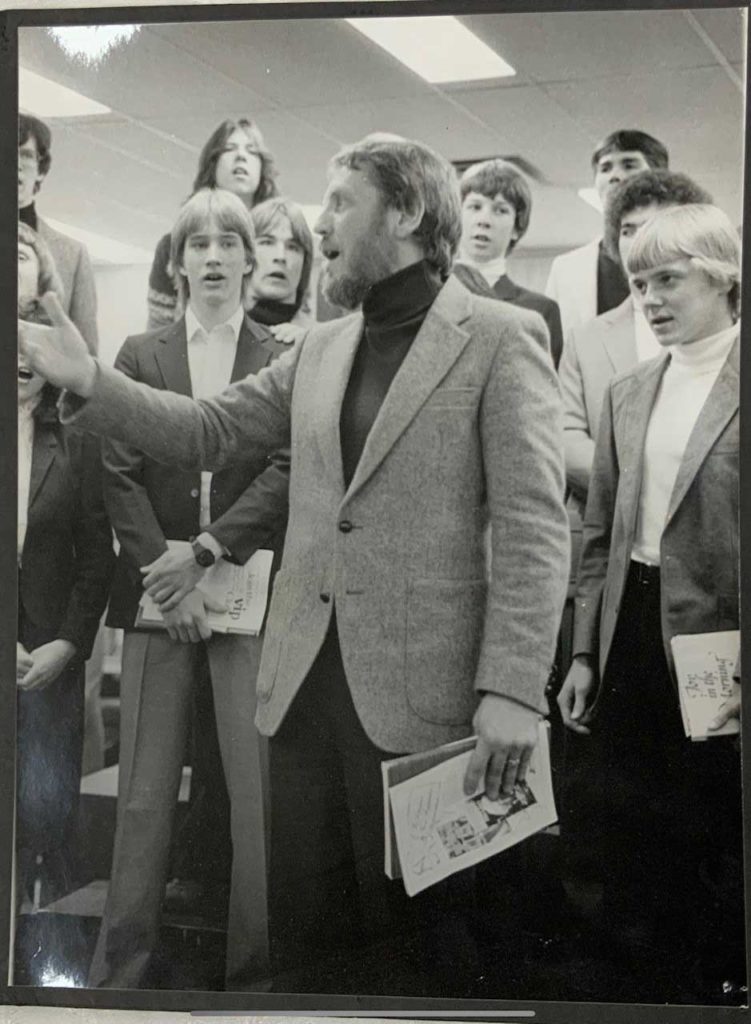

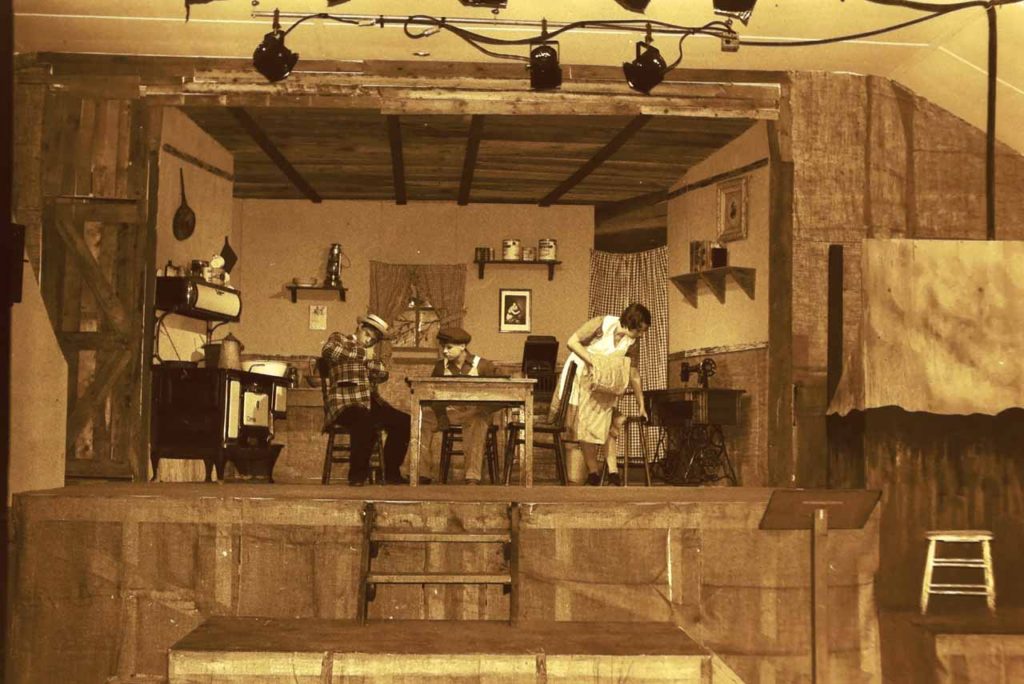

In the summer of 1973 LaVerne Erickson, a music and visual arts teacher started Rosebud Camp of the Arts as a summer outreach program for Calgary youth. By 1977 the program was developed into Rosebud Fine Arts High School combining academics, arts, and work experience. As part of Rosebud’s centennial in the summer of 1983 the School’s drama department, led by Allan DesNoyers launched the Rosebud Historical Music Theatre. Allen’s play, Commedia Del’ Arte was presented on an outdoor stage along with a country-style buffet and musical entertainment.

From those beginnings Rosebud Theatre now offers five professionally produced shows per year on two stages, in addition to summer concerts and special presentations. The country-style buffet and good old-fashioned Rosebud hospitality has evolved and now includes Chef Mo’s delicious buffet served in the Mercantile building before the show. The shows themselves are performed and produced by a resident company of artists and guest artists and provide apprenticeship opportunities for students from Rosebud School of the Arts, now a post-secondary theatre training school.

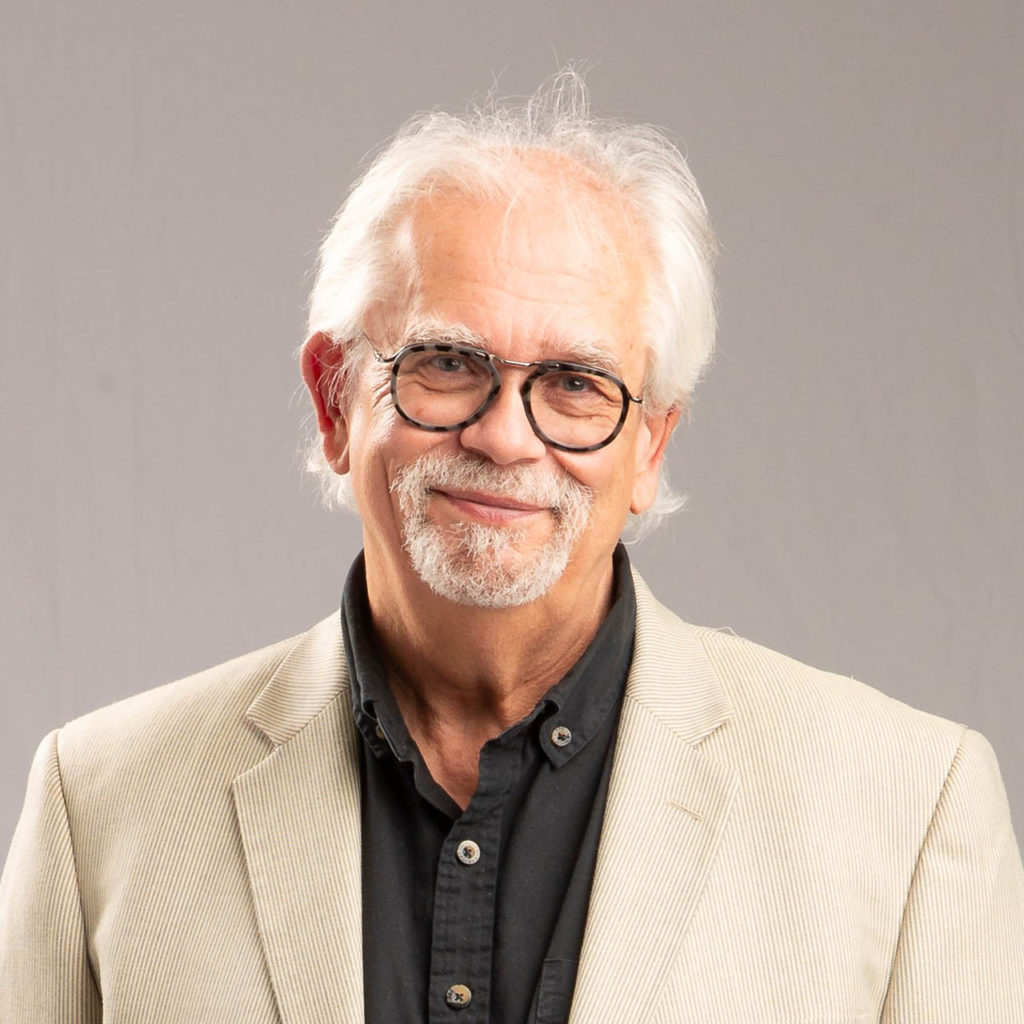

Morris Ertman who has been the Artistic Director of Rosebud Theatre for the past twenty years began his career by working extensively in Canada as a director, designer, and playwright. He has been recognized for his work with several nominations and awards including nine Elizabeth Sterling Awards in Edmonton and a Dora Mavor More Award in Toronto. Recent productions for Rosebud Theatre include The Mountain Top, A Christmas Carol, Bright Star, The Trip to Bountiful, The Sound of Music, and All is Calm: The Christmas Truce of 1914. I contacted Morris to talk with him about the early days of his career, his approach to the work, and what makes Rosebud such a special and mystical place where people gather to tell stories are share memories.

JAMES HUTCHISON

So, I read that you grew up in Millet Alberta. What are some of your memories of your childhood, and I was wondering how do you think family life and growing up in a small town shaped you as a person and an artist.

MORRIS ERTMAN

Oh, boy. Well, lots of things. I actually grew up on the farm outside of Millet Alberta. So, it’s even smaller. Well, my mom loved music and literature and was a theologian in her own right. My dad loved to build things. He would build beautiful furniture. And so, I grew up surrounded by ideas and craft. It was part of the family.

And to this day I still get up between five and five-thirty a.m. because I had to milk the cows every single morning. And so, I guess growing up on the farm taught me a little bit about discipline. It didn’t matter how late you were up the night before. Dad would knock on the door and say, “Time to get up.” And off you went.

And I would credit the absolute freedom of growing up in a rural environment with imaginative freedom. I grew up listening to the radio. Sitting in front of CBC listening to Saturday Afternoon at the Opera and symphony orchestras and imagining stories. I just think that rural environment broke open the imagination, and I met characters growing up that were worthy of a W.O. Mitchell novel. They were fantastical and interesting and nutty and made you curious about who they were.

And, of course, I went to school in small town Alberta and so you know everybody. And lots of people made room for me as a creative when I was a kid. In the church there’d be a play and, “Well, Morris likes to do that. Let’s get him to do it.” And there’s no stakes, right? Nobody’s going to live or die by the play that you do in a church or the play that you do in your high school. And so, I was free to play. Free to figure it out. And if you’re a storyteller, it is not a choice. It’s just the way you think. And you think that way because it’s put in you. It’s innate. And when there’s no stakes you just practice it. You love doing it. I can’t imagine doing anything else.

JAMES

Before we talk about the importance of mentorship at Rosebud, I understand that Robin Phillips was one of your mentors. He came from England and was the Artistic Director of the Stratford Festival from 1974 to 1980 and he led the Citadel Theatre in Edmonton between 1990 to 1995. He had a long career including productions on Broadway and in the West End and he was appointed to the Order of Canada in 2005 and in 2010 he received the Governor General’s Performing Arts Award for Lifetime Artistic Achievement. How did the two of you meet and what sort of role did he and maybe other mentors play in your life and career over the years?

MORRIS

Well, I was a young designer – an Edmonton theatre designer – as well as a director, but I met him as a theatre designer. That’s how he employed me. And I remember Margaret Mooney who basically ran the Citadel and took care of every artistic director that was there called me up one day and she said, “Morris, Robin wants to see you. Don’t screw it up.” And I knew who he was, of course, so I scrambled my portfolio together and I went in to see him and he looked at my work and he went, “Lovely darling.” And then two weeks later he handed me all the biggest shows in the season.

And I found out later that he had seen a couple of things that I had done the year before. So, I wasn’t totally new to him. And he just handed it to me. And then our working relationship grew over a period of about eight years. I designed his first operas for the Canadian Opera Company. He was incredibly generous with the work, and I was known in Edmonton, but I didn’t have a career outside of Edmonton.

And so I credit him with catapulting my career into the national spotlight and getting national work and getting an agent in Toronto and everything else. It was because of Robin. He gave me a leg up. But I also learned by watching him over the years direct shows and watching the magic with which he staged shows and in particular the way he dealt with the chorus in a musical. I probably learned the most about directing by participating in his shows as a designer.

And the other thing about him too was that he was incredibly liberating when it came to creative things. I would go to Margaret’s desk with a white paper model of a set and I’d say, “This is for Robin. It’s a preliminary idea.” I’d come back at the end of the day and there’d be a note. “Lovely, darling.” And off, we went. The biggest discussion we ever had in terms of conceptual discussion around a show was for The Music Man. He walked into the design office and said, “Gingerbread.” And I said, “Clapboard.” And he said, “Lovely, darling.” And that was the longest discussion we had conceptually about any show. And I would deliver the designs and he would jump off of them and make all kinds of magic.

JAMES

What was the magic he saw in you?

MORRIS

Well, of course, I can’t speak for him, and we never really talked about it, but I am a minimalist. I’m most interested in saying many things with one thing. The brevity of image, the brevity of staging with nothing wasted, I suspect is what we held in common. And that sensibility in terms of design came from another mentor of mine by the name of Brian Currah, who is a West End London designer who actually designed almost all the original Edward Bonds and Harold Pinters in the West End. I didn’t know that at the time.

And I once stood over him watching him draw a design for Harold Pinter’s The Birthday Party. I looked over his shoulder and he’d drawn a beam. And I was in awe. He had succeeded in speaking and telling the whole story of the play in that beam. And I think I was a minimalist already, but those guys helped. They basically confirmed and modelled things that I already had in me and then pushed them further.

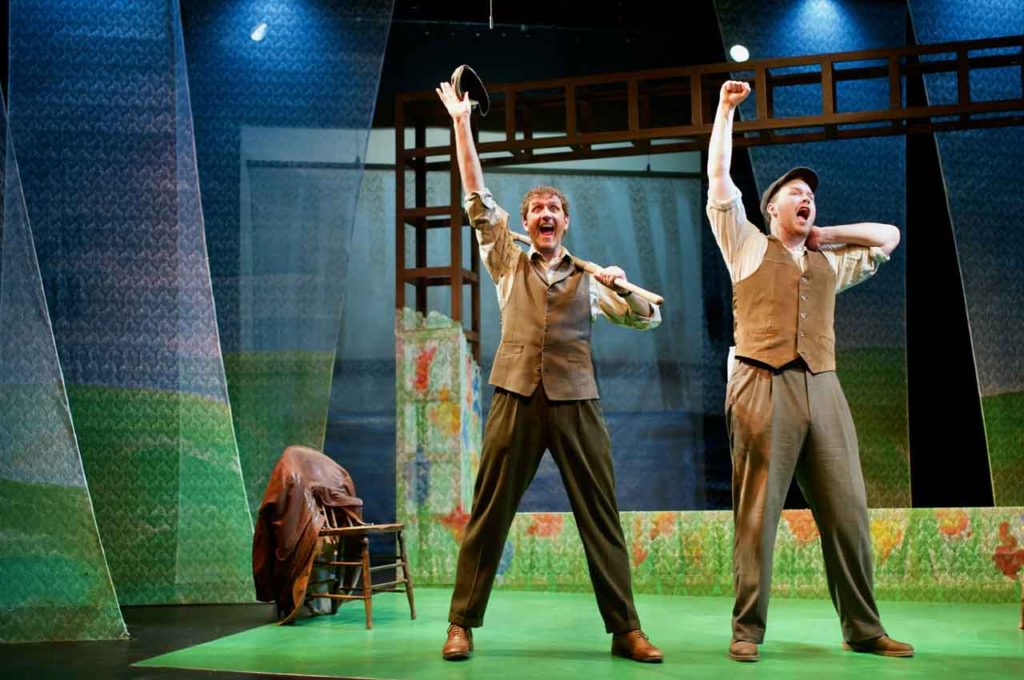

And there was W.O. Mitchell. I am going to speak his name too. You know, there’s my musical Tent Meeting, which I co-wrote with Ron Reed, but the very first draft of that play I wrote as a young theatre artist running my own company in Edmonton and I wrote that because I read Who Has Seen the Wind. And that story gave me the permission to put pen to paper. I hadn’t done so before. And since then, I’ve written a lot. Those are some pretty amazing people that lined up.

JAMES

You know since you mentioned Tent Meeting — it’s a show that you wrote many years ago — I didn’t know it was your first. But I know you’ve done various versions of it and that it’s grown and developed and I wonder what’s it like having a piece of work like that follow you through your career?

MORRIS

It’s a gift. I wrote that first version with a company of actors, some of whom – we still work together, and that was forty years ago. And so, there’s the relationships that were fostered in that development and initial performance process that are enduring. That’s been wonderful.

And then of course, Ron Reed joined me in co-writing the next draft, which is the draft that wound up being the one that was produced in the US and Canada. We just got a lot of productions out of it, and he joined me because he saw the original production and he wanted to do it on the Pacific Theatre stage. And I said, “It’s not good enough. It needs a rewrite. And I don’t have any time to rewrite it.” And Ron said, “Well, I’ll write it with you.” And so, we did. And of course, Ron Reed and I have been colleagues and friends for forty years. So those things – those relational things are part of it.

The other thing is the fact that it is really, really, really a privilege, it’s an honour that something that you penned and pulled out of the ether in one way or another wound up capturing people’s imagination and moving people. You know, it wasn’t just the songs. It was everything. And so somehow a story set in a rural Albertan religious setting made it universal. And I think that’s pretty cool. I think of it as a tribute in lots of ways to the church community I grew up in. I go, this is them. This is their love. These are their songs. So, there are lots of connections.

JAMES

Well, one of the connections is I know it was produced at Rosebud and let’s talk a little bit about that. So, you were having your career and in 1998 I believe you did Cotton Patch Gospel at Rosebud and a couple of other shows and then they offered you the Artistic Directorship in 2001. So, what did you think of Rosebud when you arrived in this little village to direct your first show and here we are now many decades later — what’s it been like to work in Rosebud – to see the growth of the community and the creation of this vibrant theatre season. What sort of journey has that been like?

MORRIS

Well, when I first produced Tent Meeting forty years ago it had its first incarnation in Edmonton and then at the Pumphouse in Calgary. And Allen Desnoyers, who was running Rosebud’s theatre adventures at the time, brought everybody in from Rosebud to see the show at The Pumphouse, and he invited me to come back out to Rosebud and do a workshop on directing.

I did, and while I was there I saw the very first play in the Opera House called When the Sun Meets the Earth, which was his show that he had written. And since, of course, we’ve done many things together. So that was my first introduction to Rosebud. And at that time it was just cool. Great. Wonderful. And after I was onto other things and that was that. But then when they asked me to come and direct Cotton Patch Gospel several things happened.

I met a company of people who were in it. The Rosebud river valley boys were really the core of it. I met a group of people and we would talk late into the night about how theatre mattered and how connecting to an audience mattered. And how having a communal relationship with an audience mattered. And some of those things were new to me because I was a jobber. I was a freelancer. And so, I think those guys woke a hunger in me to be a part of something bigger than just to do a show.

And there was a synergy that we had. And that was cool. And in that show – Cotton Patch Gospel, there was a young student by the name of Nathan Schmidt, who played the fiddle and he had no lines. I built the whole show around him. He didn’t know it. He didn’t have any lines, but I built the whole show around Nathan Schmidt and later on, you know, as we’ve talked about it, he told me he was so mad as a young student that he didn’t have any lines and he had no idea that I saw his magic, right away and I went, “Boy, this guy’s compelling.” And we built the show around him.

So, I guess one of the things I would have to say about Rosebud is that there’s a core company of artists like the core of a band. You know, U2 stuck together for how many years and made music and they were brothers, and in our case we’re brothers and sisters – we’re a band. There’s a shorthand language. We share a lot of the same sort of passions and values. And that’s a privilege to be a part of such a thing.

JAMES

You know we’re more conscious these days about honouring the Indigenous people who originally made this land their home. And I’ve read things that you’ve written where you’ve spoken about the tradition of storytelling in the valley, and I was wondering how is Rosebud connected to those Indigenous storytellers of the past and how does that legacy of storytelling live on?

MORRIS

It’s more mystical than practical in my mind. I believe the valley is a storied valley. And I’ve always had an admiration for Indigenous culture ever since I was a kid. Growing up on the land like I did, I think I have some understanding of what that means. And I think that in some kind of mystical way when we’re doing plays and telling stories in the Opera House or in the Rosebud Valley – those elders are kind of smiling upon us. Because they were storytellers. And that’s more mystical than it is anything else. And I just feel every which way we can understand our connection to those that came before us makes the work we do richer and more expansive in ways that we probably do not understand.

JAMES

I watched a short documentary about a day in the life of Rosebud by Canadian filmmakers Eric Pauls and Michael Janke. In the film you mention thin places and you mention that’s an idea that comes from Ireland. And you mention also that you love Ireland. So, I’m curious about your connection to Ireland and then how thin places relate to Rosebud and what happens here?

MORRIS

My wife Joanne and I early in our marriage before I was even finished university, we spent some time in England, and of course travelled to Ireland. And we took a fishing boat across to the Aran Islands where Synge had set his play Riders to the Sea. And I was so struck by this windswept rock that I wrote a piece called Sea Liturgy that failed miserably. But it was about the wind and it was about sacred places. And I remember we would go into these ash woods that were sacred druidic woods – and they were so amazing to me – and this is a little mystical because our yard here in Millett where we live is filled with ash trees that we didn’t plant.

And so, Ireland to me wakes magic. And there’s just a belief in the mystical. I think there is an innate understanding of the mystery of life and about being tied to the earth and the sky and everything else that I completely buy into and you get that feeling in Ireland. And so, here’s Rosebud. And the very first time I did Cotton Patch Gospel here it was a really green summer. And I remember looking out over the hills and thinking this feels a lot like Ireland. And then of course I’d read somewhere or heard somebody talk about thin places – that is a place where the membrane between heaven and earth is so thin that you can reach across.

And all of a sudden you feel like you can be in touch with the things that are intangible. I believe that I can be in touch with my parents who have passed on. I believe that the great cloud of witnesses that the apostle Paul talks about is actually true. And I think however we try to articulate it when we live our lives within the context of that mystery, I think that worlds of magic open up to us, worlds of possibility.

JAMES

As a director how do you work with actors and designers and in particular, I’m interested in how you utilize the stage at Rosebud. What’s your process like?

MORRIS

Well, the story is the thing. The actor carries the story. Those are really fundamental things for me, and I never want it to be different than that. I think human beings embodying the story is the most compelling thing on God’s green earth. And everything else that we try is not nearly as compelling as a human being spinning out the story. So, the actor is central to the aesthetic.

And I am informed by the movies. I do not know when I clued into this but you know when you watch a movie you never stop the action to change the scene. Why? Because the whole language of it is all about staying with the emotional journey of the central characters. You never drop the feeling in a good movie. So, there’s nothing extraneous. And I think I’ve spent the better part of my career trying to apply that to the stage. What is the essence of the moment that is happening in front of our eyes and how does it multiply with each beat in the story?

And in my rehearsal halls, I put a lot of emphasis with actors on the fact that everything is real. And that you can’t compartmentalize it. What just happened in the scene before – the residue of that must inform the next scene. And we don’t know where the story is going. We don’t actually know what the play is about. We just know how to begin. And of course, that beginning happens way back early on when a person is talking to designers. And I tend to choose people with an aesthetic that is evocative and simple. And my charge to designers always is – nothing can get in the way of the action of the play. We can never stop it.

MORRIS (CONT’D)

So, in The Sound of Music all of a sudden, we’re changing Maria’s clothes on stage, and we turn that into story, and it winds up spinning itself out into two changes and finally her changing von Trapp’s tie on stage just before they go off to the concert. And I didn’t know that was going to happen when we began but you enter the thing and then you’re sculpting.

And when I was a designer predominantly, I would go into an art store and I would just walk up and down the aisles. I’d buy handmade papers and things that were just beautiful. And when I think about casting, I’m assembling the most beautiful group of human beings, and I want to find out how they embody the play and how the play is embodied in them. And then I think it just goes deeper.

JAMES

I can attest to watching your shows that they flow, and that the transitions between scenes feels more like a dissolve and don’t interrupt the action. And I think that certainly influences the impact that the story and play has on the audience.

MORRIS

I think so too because the audience is tracking those characters. They’re falling in love with those human beings. They want to know with every emphatic bone in their bodies what’s happening next with those human beings. So, nothing can get in the way of that. And when we’re lucky, when it really, really, really works, the scenery becomes a metaphor, and the scenery just somehow emotionally heightens what is going on in the story.

JAMES

So, you’re educating the next group of storytellers and artists and designers and actors. How does mentorship play a role in the development of young artists here in Rosebud?

MORRIS

Well, I think it’s everything. It’s not lost on me that every electrician has to apprentice. Every mechanic has to apprentice. Every guy that takes over his parent’s farm, in a sense, has apprenticed. And so, it just makes sense that you learn the craft from the people who come before you. Of course, that was Rosebud’s philosophy right from the very beginning and I just stepped into it.

And it makes all kinds of sense. It makes sense to me that for the student when a mentor says, “Yeah, you’re on. You’ve got the goods.” Well, that’s a kind of naming. And if I look back on my own career there were many namings that happened. And those namings help you stand in this business.

And so, I think that all those namings that happen with those students when they’re working with Nathan as their acting coach or Paul Muir as an acting coach or Cassia Schramm as a voice coach or working in one of my productions, I think every single one of those namings, those challenges offered and met are what make Rosebud’s training great. And I think it’s what makes confident young people confident enough to step out there and do their thing. They are not just doing it because they made a grade, they’re doing it because people believed in them and not just people but people with credibility believed in them. You know, all of our moms and dads believe in us but in my life it took Robin and others to actually help me stand tall in the work that I do.

JAMES

I’m wondering when people come out to Rosebud and they’ve enjoyed a meal – they’ve seen a show – they’ve shared in that community experience what is it you hope audiences take away with them when they’ve experienced as you have put it – “good old fashioned emotional storytelling.”

MORRIS

Well, number one, I hope they are emotionally impacted. Either they are bawling, or they can’t stop giggling, or they can’t stop thinking about a moment in the play. We win if they can drive home and not dismiss the thing as ho-hum. Then we win. We win and when I say we I mean the audience and us win. And when an audience watches Nathan Schmidt grow from a student into a fine accomplished actor and it happens in front of their eyes – they know him – they know Cassia – they know Glenda – they know these people – I think that is invaluable. And the richer that relationship can be, the more it feels like family when people come into the valley and when they leave.

And man, there’s no greater pleasure than somebody coming up to me and saying you know when you did that play or that show and there was a moment where this happened and I just can’t forget about it – that’s it – that’s the reason for being right there. Because ultimately, I believe that when people are opened up emotionally, it’s a doorway to the mystic. I think when people are impacted by a story that actually reaches deep and by the way, it can reach deep by making you laugh your silly head off, but when it reaches deep into you and elicits a response, I actually think it changes your nature. Just like any dramatic experience in life does. And all we’re doing is we’re creating artificial experiences – stories that hopefully go as deep and as rich as life itself.

***

To find out more about Rosebud Theatre and their current season visit RosebudTheatre.com.

To find out more about Rosebud School of the Arts visit RosebudSchooloftheArts.com.